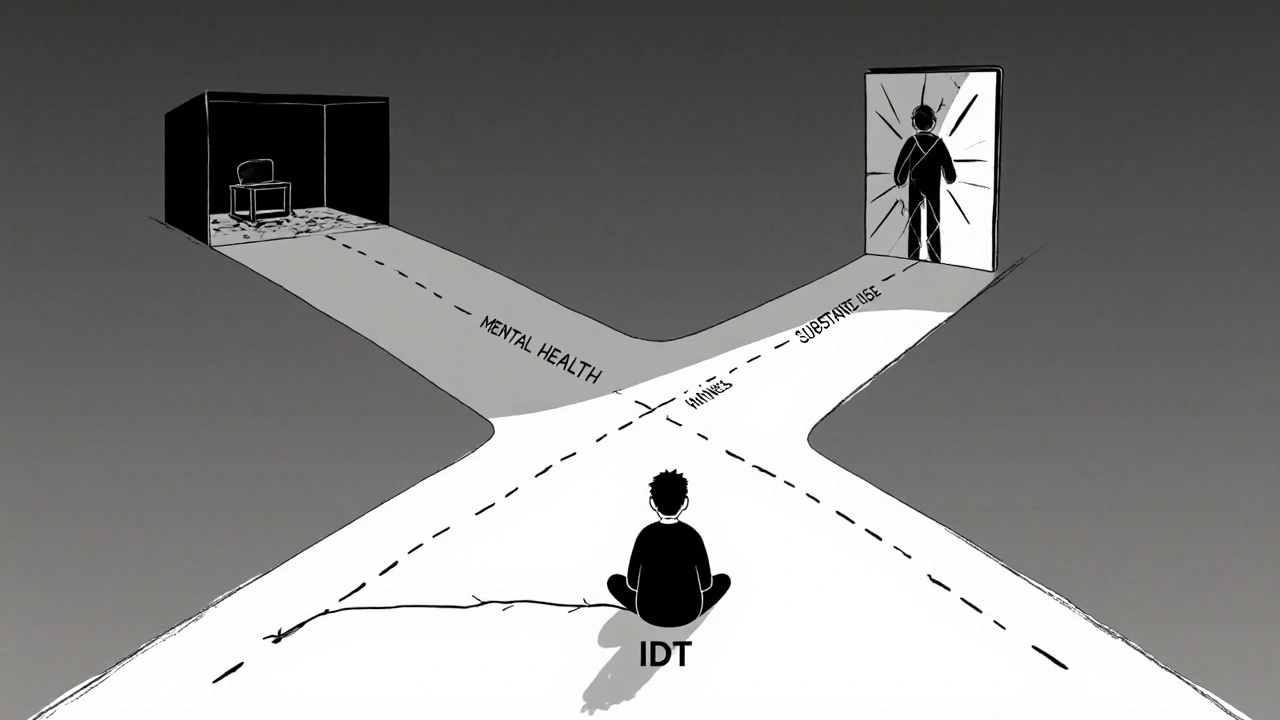

Imagine you’re struggling with depression, and every day feels heavier than the last. At the same time, you’re drinking to numb the pain-maybe not every day, but enough that it’s becoming a habit. You go to a therapist for your mood, but they don’t talk about your drinking. You see a counselor for alcohol use, but they don’t ask about your sleep, your anxiety, or why you feel so empty. This isn’t rare. It’s the norm. And it’s broken.

More than 20 million adults in the U.S. live with both a mental illness and a substance use disorder. That’s about one in every 12 people. Yet, only 6% of them get treatment that addresses both conditions at the same time. The rest are caught in a cycle: their mental health makes substance use worse, and the substance use makes their mental illness harder to manage. This isn’t just about addiction or depression-it’s about how our systems fail people who need help with both.

What Is Integrated Dual Diagnosis Care?

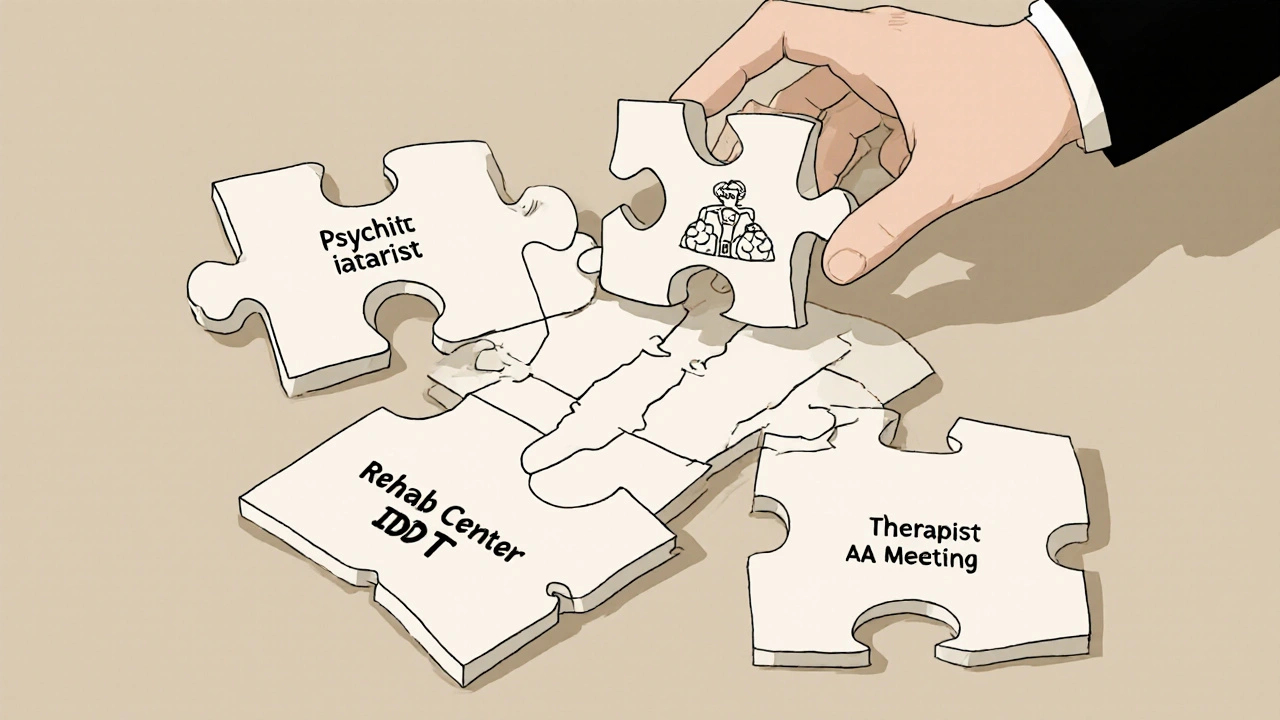

Integrated Dual Diagnosis Treatment, or IDDT, is the only approach proven to break that cycle. Unlike traditional models that treat mental illness and substance use separately, IDDT brings both under one roof-with one team, one plan, one voice. It’s not just a better way to deliver care. It’s the only way that works for people with co-occurring disorders.

Developed in the 1990s by researchers at Dartmouth and New Hampshire, IDDT was built on a simple truth: you can’t fix one without addressing the other. A person with schizophrenia who uses cocaine isn’t two separate patients. They’re one person with two interconnected problems. Treating them as separate leads to confusion, missed connections, and relapse. IDDT treats them as one.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) calls IDDT the “gold standard.” It’s backed by decades of research and endorsed by every major behavioral health organization in the U.S. The model doesn’t demand abstinence right away. It doesn’t shame people for using. It meets them where they are-and helps them move forward, step by step.

How IDDT Works: The Nine Core Components

IDDT isn’t a vague idea. It’s a structured, evidence-based system with nine specific practices that work together:

- Motivational interviewing-a conversation style that helps people find their own reasons to change, without pressure or judgment.

- Substance abuse counseling-focused on reducing harm, managing triggers, and preventing relapse, even if someone isn’t ready to quit completely.

- Group treatment-where people with similar struggles support each other in a safe, structured setting.

- Family psychoeducation-teaching loved ones how to understand both the mental illness and the substance use, so they can offer real support.

- Participation in self-help groups-like Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous, but adapted to include mental health recovery.

- Pharmacological treatment-medications for depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or opioid dependence, carefully coordinated to avoid harmful interactions.

- Health promotion-helping people improve sleep, nutrition, exercise, and medical care, because physical health affects mental health and vice versa.

- Secondary interventions-for those who aren’t responding to standard approaches, offering more intensive support.

- Relapse prevention-not just avoiding drugs, but recognizing early warning signs of worsening mental health and acting before crisis hits.

Each of these isn’t optional. They’re all required for the model to work. A team trained in both mental health and addiction delivers them together. No handoffs. No referrals. No confusion.

Why Parallel Treatment Fails

For years, the default was to treat one disorder first, then the other. If you had depression and alcohol use, you’d go to a psychiatrist, then later to a rehab center. Or vice versa. This is called parallel or sequential treatment.

It sounds logical. But it doesn’t work.

Why? Because the two conditions feed each other. Someone with PTSD might drink to sleep. If you only treat the drinking, the nightmares come back-and so does the drinking. If you only treat the PTSD, the person might self-medicate with opioids because they still feel unsafe in their own body.

Studies show parallel treatment is expensive, confusing, and ineffective. People drop out. They get lost between systems. They hear conflicting messages: “Stop drinking” from one provider, “Here’s a new antidepressant” from another. No one connects the dots.

IDDT fixes this by having one provider-someone trained in both fields-understand the full picture. They see how anxiety leads to cannabis use, how psychosis increases isolation, how trauma fuels binge drinking. They treat the whole person, not the symptoms in isolation.

What the Research Shows

A 2018 randomized trial involving 154 patients with severe mental illness and substance use disorders found that after IDDT, participants used alcohol and drugs significantly fewer days per month. That’s not a small change-it’s life-altering.

But here’s the catch: while substance use went down, other outcomes didn’t improve as much-like mood symptoms, social functioning, or motivation. Why? Because the training wasn’t deep enough. Clinicians got a three-day workshop. That’s not enough to master motivational interviewing or understand the complex interplay between bipolar disorder and stimulant use.

Another study from the Washington State Institute for Public Policy found IDDT reduced alcohol use disorder symptoms by 16.5% and illicit drug use symptoms by 20.7%. But the cost to deliver it was high. The benefit-cost ratio was less than 1, meaning for every dollar spent, only about 50 cents in measurable benefits were returned. That doesn’t mean it doesn’t work. It means we’re not funding it right.

People who get IDDT report feeling heard. They don’t feel like they’re jumping between two worlds. They get one consistent message: “Your mental health matters. Your substance use matters. We’re here for both.” That alone improves engagement. And engagement is the biggest predictor of recovery.

The Implementation Gap

Here’s the hardest truth: IDDT works. But fewer than 1 in 10 programs in the U.S. actually offer it the way it’s supposed to be done.

Why? Three big reasons:

- Training is inadequate. Most clinicians are trained in either mental health or addiction-not both. Learning to treat schizophrenia and opioid dependence together takes time, supervision, and ongoing coaching.

- Funding is fragmented. Mental health services are often paid for by Medicaid. Substance use programs rely on different grants. Integrating them means navigating two broken systems.

- Organizations resist change. It’s easier to keep doing things the old way. Hiring new staff, retraining teams, changing paperwork-it’s messy. And many leaders don’t see the long-term savings.

Yet, the cost of not doing it is higher. People with untreated co-occurring disorders are more likely to be hospitalized, jailed, homeless, or die from overdose. The real cost isn’t in program budgets-it’s in emergency rooms, police calls, and funeral expenses.

What Needs to Change

Fixing this isn’t about better therapy. It’s about better systems.

First, training must go beyond a three-day workshop. Clinicians need ongoing supervision, case consultations, and access to mentors who’ve done this work for years.

Second, funding must be aligned. Medicaid and Medicare need to reimburse integrated care as a single service-not split it into two separate billing codes. States that have done this, like Oregon and Minnesota, have seen higher adoption rates.

Third, leadership must demand it. Hospitals, clinics, and community centers need to make integrated care a priority-not an add-on. That means hiring staff with dual expertise, designing intake forms that screen for both conditions, and measuring outcomes that matter to patients: fewer hospital visits, more stable housing, longer periods of sobriety.

The good news? We know how to do this. We’ve done it in pilot programs across the country. The data is clear. The model is proven. The only thing missing is the will to scale it.

What You Can Do

If you or someone you care about is struggling with both mental illness and substance use, ask: “Do you treat both here?” If the answer is no, keep looking. Demand better. Integrated care exists-it’s just not everywhere.

If you’re a clinician, advocate for training. Push your organization to adopt IDDT. Start small: screen every patient for substance use. Learn motivational interviewing. Collaborate with addiction specialists.

If you’re a policymaker, fund integrated programs. Align payment systems. Support workforce development. The return isn’t just in dollars-it’s in lives.

Recovery isn’t about choosing between mental health and sobriety. It’s about healing both at the same time. And it’s possible.

What is the difference between integrated treatment and parallel treatment?

Integrated treatment means one team treats both mental illness and substance use at the same time, using one plan and one set of providers. Parallel treatment means two separate teams, two separate programs, and two separate plans-often leading to confusion, missed care, and higher relapse rates.

Can someone recover from both a mental illness and addiction?

Yes. Many people do. Recovery doesn’t mean perfection. It means managing symptoms, reducing harm, building support, and finding purpose. Integrated Dual Diagnosis Treatment gives people the tools to do that-without having to choose between their mental health and their sobriety.

Is abstinence required in IDDT?

No. IDDT uses a harm reduction approach. If someone isn’t ready to stop using substances, the focus shifts to reducing risks-like avoiding injection, not mixing drugs with medication, or staying safe during withdrawal. The goal is progress, not perfection.

How do I find an IDDT program near me?

Start by calling your local mental health clinic or community health center and asking if they offer integrated treatment for co-occurring disorders. You can also contact SAMHSA’s National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP for referrals. Look for programs that mention dual diagnosis, co-occurring disorders, or IDDT in their services.

Why don’t more providers offer IDDT if it’s so effective?

Because it’s harder and more expensive to run. It requires staff trained in two fields, coordinated scheduling, shared records, and funding that doesn’t split care into separate billing codes. Many organizations lack the resources or leadership support to make the change-even though it saves money long-term by reducing hospitalizations and emergency care.

8 Comments

Wow-this is the most comprehensive breakdown of IDDT I’ve ever seen. Seriously, the nine components? Perfectly laid out. I’ve worked in community mental health for 12 years, and I’ve seen how fragmented care destroys people. One guy I knew? Treated for bipolar with lithium, then sent to a rehab that told him to stop all meds-so he relapsed, got hospitalized, and lost his apartment. No one talked to each other. IDDT isn’t just ideal-it’s ethical. And the harm reduction piece? Crucial. Abstinence isn’t the goal; stability is. You don’t fix a broken leg by ignoring the infection.

Bro, this hits different. In India, if you’re depressed and drinking, you’re either ‘weak’ or ‘a drunk’-no middle ground. No one says, ‘Hey, maybe your trauma’s driving the bottle.’ We don’t even have the vocabulary for co-occurring disorders. I wish someone had told my cousin this before he OD’d. IDDT isn’t just treatment-it’s dignity. And if we can’t fund it here? We’re not broken-we’re cruel.

Oh please. Another American healthcare fantasy. You think this ‘gold standard’ works in the real world? We can’t even get people to take their antidepressants, and now you want to train clinicians in two fields? Give me a break. Taxpayers are already drowning in mental health costs. This is just another bureaucratic money pit wrapped in feel-good jargon.

This is why we’re failing. You say ‘meet them where they are’-but that’s just letting people stay addicted. No one should be allowed to drink while on antipsychotics. It’s dangerous. And why aren’t we forcing abstinence? That’s the only real solution. I’ve seen too many people use ‘harm reduction’ as an excuse to keep using. It’s not compassion-it’s enabling.

One must contemplate the epistemological framework underpinning IDDT. The Cartesian dualism inherent in traditional paradigms-mind versus body, psyche versus substance-has rendered treatment modalities fundamentally incoherent. IDDT, as a phenomenological synthesis, attempts to dissolve the ontological boundary between psychiatric symptomatology and behavioral dependency. Yet, the institutional inertia of siloed funding structures remains an insurmountable hermeneutic obstacle. The model is theoretically sound, yet pragmatically unattainable within the current neoliberal healthcare apparatus.

I’ve seen this work. In a rural clinic in Ohio, we started screening everyone for substance use during intake. One woman, diagnosed with PTSD, had been hiding her opioid use for years. When the same provider talked to her about both, she cried and said, ‘No one’s ever asked if the pills were helping me sleep.’ That’s all it took. One conversation. One team. One person who saw her whole self.

Thank you for writing this. I’m a social worker, and I’ve spent years begging my agency to adopt IDDT. We got a grant last year to train two staff in dual diagnosis. It’s not perfect yet-but last month, a client who’d been in and out of ERs for three years showed up sober, got a job, and started going to AA meetings with his therapist. That’s not magic. That’s integrated care. It’s slow. It’s hard. But it’s worth it.

So… IDDT works. But nobody does it. Why? Because nobody wants to pay for it. And nobody wants to admit that the whole system is built on ignoring people until they’re a crisis. We’re not broken because we lack resources-we’re broken because we don’t care enough to fix it.