When a patient says, "This generic pill makes me feel different," it’s not just a complaint-it’s a red flag. And the pharmacist listening is often the first-and sometimes only-person who can turn that observation into a life-saving report. Adverse event reporting isn’t optional for pharmacists. It’s a core part of their job, especially when it comes to generic medications. Many assume generics are identical to brand-name drugs. But that’s not always true. Small differences in fillers, coatings, or manufacturing can trigger unexpected reactions. And when they do, pharmacists are on the front lines.

Why Generic Medications Need Special Attention

Generic drugs are approved because they’re "therapeutically equivalent" to brand-name versions. That means they contain the same active ingredient, dose, and route of administration. But equivalence doesn’t mean sameness. The inactive ingredients-like dyes, preservatives, or binders-can vary. For most people, that’s fine. For others, it’s enough to cause a rash, dizziness, nausea, or worse.

Take a patient switching from one generic version of levothyroxine to another. They might feel fatigued, gain weight, or have heart palpitations. A prescriber might assume it’s just "adjustment." But a pharmacist who’s seen this pattern before knows: it could be an excipient reaction. One study found that 18% of patients reported noticeable differences after switching generic brands, with 37% of those cases involving symptoms severe enough to prompt a doctor visit. Yet only 1 in 5 of those cases ever made it into an official adverse event report.

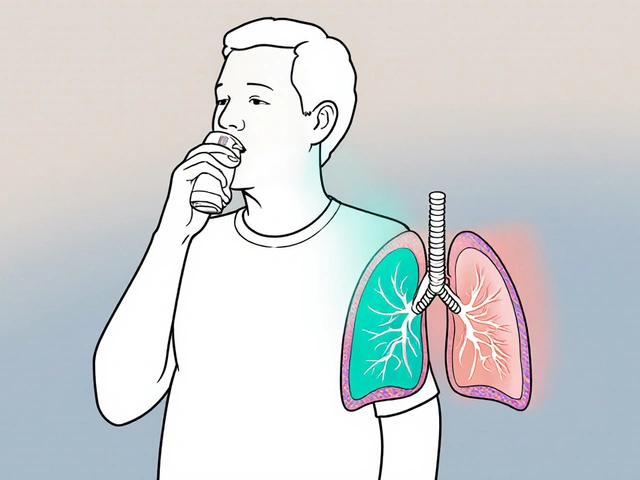

This isn’t just about discomfort. In rare cases, these differences can lead to hospitalization, organ damage, or even death. And because generics are often used by older adults, low-income patients, and those on multiple medications, the stakes are higher. Pharmacists are trained to spot these patterns. They’re the ones who see the full picture: the patient’s history, the exact product name on the bottle, the timing of symptoms, and the refill patterns. That’s why their role in reporting is so critical.

What Pharmacists Are Legally Required to Do

There’s no single federal law in the U.S. that forces pharmacists to report adverse events. But that doesn’t mean they’re off the hook. Many states have clear rules. In British Columbia, pharmacists must notify the patient’s doctor, update the PharmaNet record, and report the reaction to Health Canada. In New Jersey, consultant pharmacists must document adverse reactions and medication errors before their shift ends.

The FDA doesn’t require reporting-but it strongly urges it. The agency’s FAERS database (the main U.S. system for tracking drug safety) gets over 2 million new reports every year. But here’s the kicker: 98% of those come from drug manufacturers. That means most reports start with a pharmacist telling a patient, "Write this down," or logging it into a system. If pharmacists don’t report, the data doesn’t get in.

And it’s not just about serious reactions. Even "unexpected" side effects-like unusual headaches, sleep changes, or mood swings-should be reported if they’re new or worse than expected. The FDA defines serious adverse events as those that cause death, hospitalization, disability, birth defects, or require medical intervention. But the real value in reporting comes from catching the early, subtle signals before they become crises.

How Pharmacists Actually Report Adverse Events

Reporting isn’t complicated-but it can be time-consuming. Most pharmacists use one of two paths:

- MedWatch Online (FDA’s web portal): This is the most common route for community pharmacists. It takes about 15-30 minutes to complete a full report, including patient details, drug name, reaction description, and timeline.

- Electronic Health Record (EHR) systems: In hospitals and clinics, many EHRs have built-in reporting tools that auto-fill data from the pharmacy system. This cuts reporting time by nearly half.

But here’s the problem: 78% of community pharmacists say they don’t have enough time during the day to do this properly. A 2021 survey found that nearly two-thirds of pharmacists skipped reporting because they were too busy filling prescriptions or answering patient questions. And when they do report, they often leave out key details-like the exact generic manufacturer or the patient’s other medications-making it harder for regulators to spot patterns.

Some states are fixing this. California and Texas piloted systems that integrated reporting directly into pharmacy management software. Pharmacists now click a button during the dispensing process, and the system auto-populates the report. Reporting time dropped from 25 minutes to under 15 minutes. Patient safety improved. And pharmacists? They actually started reporting more.

Why Under-Reporting Is a Silent Crisis

Health Canada estimates that only 5-10% of all adverse drug reactions are ever reported. For generics? The number is likely even lower. Why? Three reasons:

- Assumption of safety: Many pharmacists assume generics are "just as safe" as brand-name drugs. So if a patient has a reaction, they think, "It’s probably just coincidence."

- Lack of training: Most pharmacy schools don’t require deep training in pharmacovigilance. Pharmacists learn how to dispense, not how to detect subtle safety signals.

- Confusion over responsibility: Some think reporting is the doctor’s job. Others think it’s the manufacturer’s. But the truth? It’s the pharmacist’s.

Dr. Michael Cohen from the Institute for Safe Medication Practices says it plainly: "When patients react to generics, pharmacists are often the first to notice the real issue-something about the formulation, not the drug itself." That insight gets lost without reporting.

And when reports are missing, regulators can’t act. A 2022 study in the Journal of the American Pharmacists Association showed that when pharmacists were trained and given tools to report, adverse event documentation jumped by 37%. But only 28% of those pharmacists reported non-serious reactions-even though those are the ones that often lead to bigger problems later.

What’s Changing-and What’s Coming

The tide is turning. The FDA’s Sentinel Initiative now includes data from community pharmacies to monitor real-time drug safety. The European Medicines Agency made reporting mandatory for all healthcare workers in 2012. Result? A 220% increase in reports. Countries that did this saw earlier detection of dangerous drug batches, fewer hospitalizations, and faster recalls.

Here in the U.S., momentum is building. Analysts predict that by 2025, 75% of states will adopt rules similar to British Columbia’s-making adverse event reporting a legal duty for pharmacists, not just a suggestion. Some states are already testing mandatory reporting for high-risk drugs like anticoagulants and seizure medications.

Technology is helping too. New tools let pharmacists report with one click. Mobile apps let patients self-report symptoms, which pharmacists can then verify and submit. AI systems are being tested to flag unusual patterns in pharmacy records-like a sudden spike in reports of dizziness after a specific generic batch.

What Every Pharmacist Should Do Today

You don’t need to wait for a law to change. Here’s what you can do right now:

- Ask patients: After filling a new generic, ask: "Has anything changed since you started this?" Don’t wait for them to bring it up.

- Record everything: Note the manufacturer, lot number, and exact product name-even if it’s just in your notes. That detail matters.

- Report even small things: A new rash, unusual fatigue, or nausea after a switch? Report it. The FDA needs those signals.

- Use the tools: If your pharmacy has an integrated reporting system, use it. If not, go to MedWatchOnline.FDA.gov. It takes less than 20 minutes.

- Train your team: Make sure every tech and pharmacist knows how to report. Make it part of your daily checklist.

Generic drugs save billions of dollars. But they’re not risk-free. And the people who see the most of them-pharmacists-are the ones who can make the biggest difference. Reporting isn’t paperwork. It’s protection. For patients. For the system. For the future of safe medication use.