When a patient takes a pill that combines two drugs - say, blood pressure medication plus a diuretic - they expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But for generic versions of these combination products, proving they’re just as effective isn’t as simple as comparing one drug to another. The science behind bioequivalence gets messy fast when you’re dealing with two or more active ingredients, complex delivery systems, or devices that deliver the drug. And that’s where things go off-track for many generic manufacturers.

Why Bioequivalence for Combination Products Is Harder Than It Looks

Bioequivalence means two drug products deliver the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream at the same rate. For a single-drug tablet, this is straightforward: give 24 healthy volunteers the brand and generic, measure blood levels over 24 hours, and check if the results fall within 80-125% of each other. But when you combine two drugs - like metformin and sitagliptin for type 2 diabetes - the interaction changes everything. One drug might slow down how fast the other is absorbed. Or the tablet’s coating might affect how the two ingredients dissolve together. That’s why regulators now require generic makers to prove bioequivalence not just to the combo product, but also to each individual drug taken alone.

This isn’t just theory. In 2023, the FDA reported that 35-40% of initial applications for modified-release fixed-dose combinations (FDCs) failed bioequivalence testing. That’s nearly half of all submissions getting rejected because the numbers didn’t line up. And it’s not because the generic is bad - it’s because the testing method doesn’t always capture what’s really happening in the body.

Topical Products: Measuring What You Can’t See

Imagine a cream that treats eczema with two active ingredients: one that reduces inflammation, another that repairs skin. How do you prove the generic version delivers the same amount into the top layer of skin? You can’t just swallow it or inject it. The FDA requires tape-stripping - peeling off 15-20 layers of skin with adhesive strips - then measuring how much drug is in each layer. But here’s the problem: no one agrees on how deep to go, how much tape to use, or even how to analyze the samples. One lab might use LC-MS/MS; another might use HPLC. Results vary by up to 30% between labs.

One generic company spent 18 months trying to get approval for a generic version of calcipotriene/betamethasone dipropionate foam. They ran three bioequivalence studies. All failed. Why? The drug penetrated the skin inconsistently between batches. The brand product had a stable delivery profile. The generic didn’t. Without a standardized method, developers are flying blind.

Drug-Device Combos: It’s Not Just the Drug - It’s the Delivery

Take an inhaler. It’s not enough to prove the drug in the canister is the same. You have to prove the patient can use it the same way. A slight difference in the nozzle size, the button pressure, or the timing of the inhalation can change how much drug reaches the lungs. The FDA requires aerosol particle size distribution to stay within 80-120% of the reference product. But even that’s not enough. In 2024, 65% of complete response letters from the FDA cited problems with user interface - meaning patients using the generic inhaler didn’t get the same dose because the device felt different.

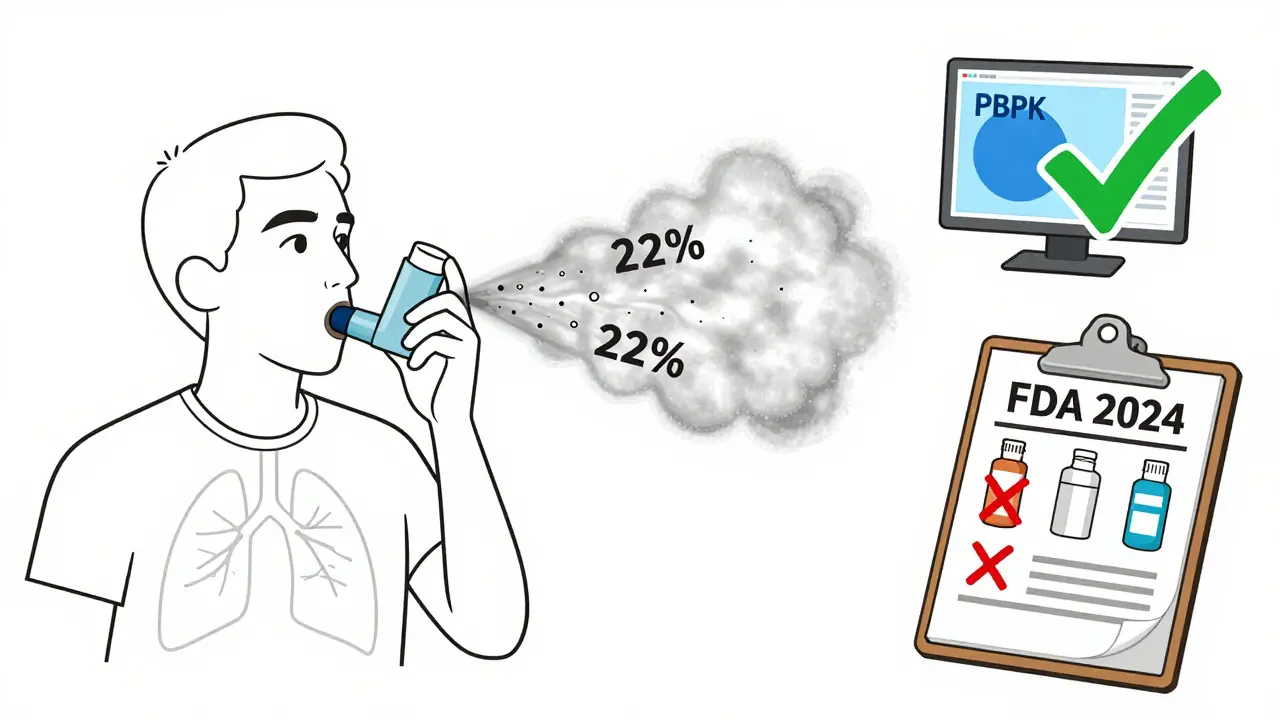

One study found that patients using a generic inhaler with a slightly stiffer button pressed it too slowly, reducing lung deposition by 22%. That’s not bioequivalence. That’s a clinical risk. And it’s why device testing now takes up nearly half the development budget for inhalers and auto-injectors.

Why Generic Companies Are Struggling

Developing a simple generic pill might cost $5 million and take two years. A complex combination product? That jumps to $15-25 million and 3-5 years. And that’s before you even start testing. Bioequivalence studies alone account for 30-40% of the total cost. You need specialized labs, trained staff, and equipment like LC-MS/MS systems that cost $500,000 each. Smaller companies can’t afford this. Only 12% of companies with fewer than 200 employees have ever successfully brought a complex product to market.

Teva and Viatris both reported in public filings that over 40% of their development failures were tied to bioequivalence issues. One company submitted 11 applications for FDCs between 2020 and 2023. Only two cleared first-cycle approval. The rest got stuck in review limbo - sometimes for over two years - because FDA reviewers in different divisions gave conflicting feedback.

What’s Being Done to Fix It

The FDA isn’t ignoring the problem. Since 2021, they’ve launched the Complex Generic Drug Products Initiative, which includes:

- 12 product-specific bioequivalence guidances (covering inhalers, topical creams, and FDCs)

- 17 approved ANDAs using physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling instead of full clinical trials

- A pilot program with NIST to create reference standards for inhaler performance

PBPK modeling is a game-changer. Instead of testing on 60 people, companies can simulate how the drug behaves in a virtual population based on physiology, absorption rates, and metabolism. Simulations Plus reported that PBPK reduced clinical trial needs by 30-50% in approved cases. The FDA accepted this method for HIV FDCs like dolutegravir/lamivudine in 2024 - a big win.

There’s also a push for in vitro-in vivo correlation (IVIVC) for topical products. Early data from 2024 shows that tape-stripping data can predict in vivo performance with 85% accuracy. If this holds up, it could cut development time by years.

The Bigger Picture: Cost, Access, and Delayed Generics

Generic drugs saved the U.S. healthcare system $373 billion in 2020. But that savings doesn’t reach patients when complex products get stuck. In 2023, the average approval time for a complex product was 38.2 months - more than double the 14.5 months for simple generics. The global market for complex generics hit $112.7 billion last year, and it’s growing at 7.2% per year. Yet 45% of these products still have no generic alternative - and won’t for years, if ever.

Why? Patent thickets. Brand companies keep filing new patents on minor changes - like a new coating or a different ratio of ingredients - to delay generics. Between 2019 and 2023, litigation over drug-device combos rose 300%. One case delayed generic entry for over two years.

And it’s not just the U.S. The EMA requires additional clinical data for 23% of complex product submissions, forcing companies to run duplicate studies in Europe. That adds 15-20% to development costs. No other region has a consistent, predictable path.

What’s Next

The FDA plans to release 50 new product-specific guidances by 2027, starting with respiratory products - where 78% of submissions currently fail bioequivalence testing. The goal isn’t just to approve more generics. It’s to make the rules clear enough that small companies can play.

For patients, this matters. A generic version of a combination drug can cut costs by 80%. But if the generic doesn’t work the same way, it’s not a savings - it’s a risk. The system is slowly adapting. Better modeling. Standardized testing. Clearer rules. But until then, the path from lab to pharmacy shelf remains long, expensive, and uncertain.

What is a fixed-dose combination (FDC) product?

A fixed-dose combination (FDC) is a single dosage form that contains two or more active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) in fixed proportions. Common examples include drugs for HIV (e.g., dolutegravir/lamivudine), hypertension (e.g., amlodipine/valsartan), and diabetes (e.g., metformin/sitagliptin). FDCs are designed to simplify dosing, improve adherence, and sometimes enhance therapeutic effect. But for generics, proving bioequivalence to both individual components and the combined product adds major complexity.

Why can’t generic manufacturers just copy the brand’s formula?

Because the formula isn’t always the issue - it’s how the ingredients interact. Two drugs that work fine separately might behave unpredictably when combined. One might change the pH of the tablet, affecting how the other dissolves. Or a coating meant to control release might interfere with absorption of the second drug. Generic makers can’t just reverse-engineer the brand’s tablet; they have to rebuild it from scratch, ensuring every interaction behaves the same way. That’s why many fail even when their ingredients are identical.

How do regulators test bioequivalence for topical creams?

The FDA currently requires tape-stripping: applying adhesive strips to the skin to remove layers of the stratum corneum (the outermost skin layer), then measuring how much drug is in each layer. But there’s no standard on how many strips to use, how deep to go, or how to analyze the samples. Labs use different methods - some use mass spectrometry, others use chromatography - leading to inconsistent results. This lack of standardization is why many topical product applications get rejected or delayed.

What role does PBPK modeling play in bioequivalence testing?

Physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling uses computer simulations to predict how a drug moves through the body based on physiology, absorption, metabolism, and distribution. For complex products, it can replace or reduce the need for large-scale human trials. The FDA has accepted PBPK in 17 approved generic applications as of mid-2024. It’s especially useful for FDCs and modified-release products, where traditional blood sampling can’t capture interactions. Companies using PBPK report cutting clinical trial costs by 30-50%.

Why do inhaler generics often fail bioequivalence?

Because the device matters as much as the drug. Even if the chemical formulation matches the brand, a different nozzle size, button resistance, or spray timing can change how much drug reaches the lungs. The FDA requires aerosol particle size to stay within 80-120% of the reference product. But real-world use - how patients inhale, how hard they press - varies. In 2024, 65% of FDA rejection letters cited user interface problems. A generic inhaler might work perfectly in the lab but fail in a patient’s hand.

What’s the biggest barrier for small generic companies?

Cost and complexity. Developing a complex product requires $15-25 million and 3-5 years. Bioequivalence testing alone demands specialized labs, expensive equipment like LC-MS/MS systems ($500,000 each), and staff with years of training. Smaller companies lack the resources to invest in this. Many can’t even get consistent feedback from regulators - different FDA divisions give conflicting guidance. As a result, 89% of generic companies surveyed in 2023 said current bioequivalence requirements are "unreasonably challenging" for small players.

How long does it take to get a combination product approved?

On average, complex combination products take 38.2 months for first-cycle approval - more than double the 14.5 months for simple generics. Some take over five years, especially if multiple bioequivalence studies fail. The delay isn’t just due to science - it’s also because of regulatory inconsistency, lack of clear guidelines, and patent litigation. In 2023, 78 industry submissions to the FDA cited "lack of clear bioequivalence pathways" as the top barrier.