When a generic drug company wants to prove their version of a medicine works just like the brand-name version, they don’t test it on thousands of people. They use a smarter, leaner method called a crossover trial design. This isn’t just a statistical trick-it’s the backbone of how regulatory agencies like the FDA and EMA decide if a generic drug is safe and effective enough to hit the market. And it’s been the gold standard for over 30 years.

Why Crossover Designs Rule Bioequivalence Studies

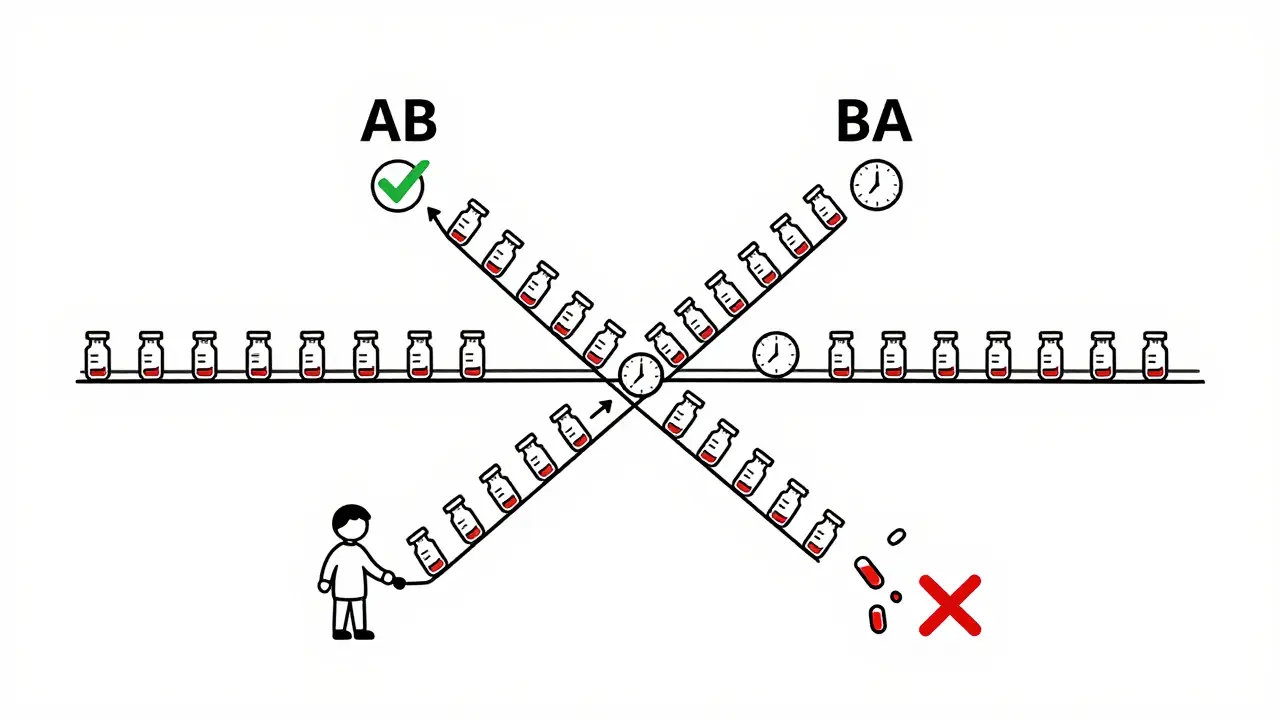

Imagine you’re trying to compare two painkillers. If you give one group Drug A and another group Drug B, any differences you see could be because of the people themselves-not the drugs. One group might be younger, healthier, or metabolize drugs faster. That’s noise. Crossover designs cut through that noise by making each person their own control. In a typical crossover study, every participant takes both the test drug (the generic) and the reference drug (the brand-name version), but in a different order. Half get the generic first, then the brand. The other half get the brand first, then the generic. This way, any differences in how the body responds are due to the drug itself, not who’s taking it. This approach slashes the number of people needed. If the variation between people is high-say, due to age, weight, or metabolism-a parallel study might need 72 volunteers to get reliable results. A crossover study? Just 24. That’s a 75% reduction in cost, time, and effort. For companies making generics, that’s not just efficient-it’s essential.The Standard 2×2 Design: How It Actually Works

The most common crossover setup is called the 2×2 design. It’s simple: two treatment periods, two sequences.- Sequence AB: Test drug → Washout → Reference drug

- Sequence BA: Reference drug → Washout → Test drug

What Happens When the Drug Is Highly Variable?

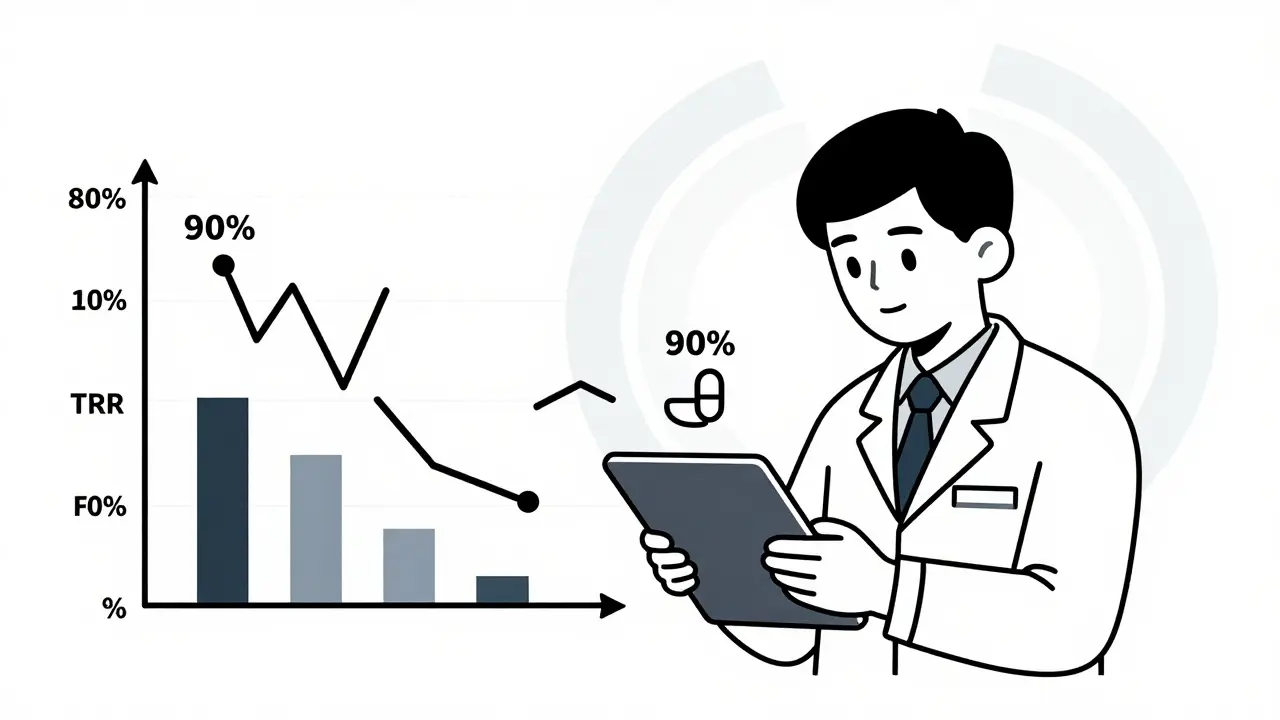

Not all drugs behave the same. Some, like warfarin or clopidogrel, show huge differences in how they’re absorbed from person to person-even the same person on different days. These are called highly variable drugs (HVDs), with an intra-subject coefficient of variation (CV) over 30%. Here’s the problem: a standard 2×2 design doesn’t have enough power to detect small differences in HVDs without needing hundreds of participants. That’s not practical. So regulators introduced replicate designs. There are two types:- Partial replicate (TRR/RTR): The test drug is given twice, the reference once. Participants get either TRR or RTR.

- Full replicate (TRTR/RTRT): Both drugs are given twice. Participants get TRTR or RTRT.

Why Washout Periods Are the Make-or-Break Factor

A study in 2021 failed because the team assumed the drug’s half-life was 12 hours. It was actually 18. They waited 60 hours-five half-lives-instead of 90. Residual drug was still in participants’ systems during the second period. The data was garbage. The study had to be redone. Cost: $195,000. Washout isn’t guesswork. It’s science. Companies must validate it using pharmacokinetic data from prior studies or pilot trials. They need proof that drug concentrations dropped below the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) before the next dose. If they don’t, regulators will reject the study outright. Statisticians also check for sequence effects. If people who got the test drug first respond differently than those who got the reference first-even after washout-it suggests carryover. That’s a red flag. The model must include sequence, period, and treatment as fixed effects, with subject as a random effect. SAS or R packages like ‘bear’ are used to run these models. But if you don’t know how to set them up right, you’ll get false results.Replicate Designs Are Taking Over-Here’s Why

In 2015, only 12% of HVD approvals used RSABE with replicate designs. By 2022, that jumped to 47%. Why? Because more drugs are becoming complex. Think delayed-release tablets, inhalers, or injectables with unusual absorption patterns. These aren’t simple pills you can swap out easily. CROs like PAREXEL and Charles River now run 75-80% of their bioequivalence studies using crossover designs. Of those, 22% use partial replicates, 10% use full replicates. The rest are 2×2. But the trend is clear: replicate designs are growing at 15% per year. The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance now allows 3-period designs for narrow therapeutic index drugs-like lithium or phenytoin-where even tiny differences can be dangerous. The EMA is expected to formally recommend full replicate designs for all HVDs in 2024.

What Goes Wrong-and How to Avoid It

The most common mistake? Underestimating variability. Companies assume a drug’s CV is 20% when it’s actually 40%. They design a 2×2 study with 24 subjects. The results? Wide confidence intervals. The drug fails. They have to restart with a replicate design-double the cost, double the time. Another pitfall: missing data. If someone drops out after the first period, their data is useless in a crossover design. You can’t just average the remaining people. The whole point is comparing each person to themselves. Missing one period breaks that. That’s why dropout rates are tracked closely-and why studies often enroll 10-15% extra participants. Training matters too. Biostatisticians need specialized knowledge. A general clinical trial statistician might not know how to handle sequence-by-period interactions or how to implement RSABE in SAS. Many companies now send staff for 6-8 weeks of focused training before running a study.What’s Next for Crossover Trials?

The future isn’t about replacing crossover designs-it’s about enhancing them. Adaptive designs are catching on. These let researchers look at early data and adjust the sample size mid-study. In 2018, only 8% of FDA submissions used this. By 2022, it was 23%. That’s because it saves money when variability is higher than expected. Emerging tech like wearable sensors that track drug levels continuously could one day reduce or even eliminate washout periods. Imagine a patch that measures drug concentration in real time. That could make crossover trials faster and more accurate. But for now, the old rules still apply: five half-lives, clean washout, proper modeling. Crossover trials aren’t perfect. But they’re the most efficient, reliable, and scientifically sound method we have for proving bioequivalence. They’ve saved billions in healthcare costs by making generics viable. And as long as we need safe, affordable medicines, they’ll keep running.What is the main advantage of a crossover design in bioequivalence studies?

The main advantage is that each participant serves as their own control, which eliminates differences between individuals-like age, weight, or metabolism-from affecting the results. This dramatically reduces the number of people needed for the study while increasing statistical power. For example, a crossover design may need only one-sixth the participants of a parallel design when between-subject variability is high.

Why is the washout period so important in a crossover trial?

The washout period ensures that the drug from the first treatment is completely cleared from the body before the second treatment begins. If any residue remains, it can interfere with the measurement of the second drug, leading to carryover effects. This invalidates the comparison. Regulatory guidelines require a washout of at least five elimination half-lives, and this must be proven with pharmacokinetic data.

What’s the difference between a 2×2 and a replicate crossover design?

A 2×2 crossover gives each participant one dose of the test drug and one of the reference drug, in either order. A replicate design gives each participant multiple doses of each drug-usually two. Partial replicate (TRR/RTR) gives the test drug twice and reference once; full replicate (TRTR/RTRT) gives both drugs twice. Replicate designs are used for highly variable drugs because they allow regulators to use reference-scaled bioequivalence, which adjusts the acceptance range based on how much the drug varies within a person.

When is a crossover design not suitable for a bioequivalence study?

Crossover designs are unsuitable for drugs with extremely long half-lives-like those over two weeks-because the required washout period would be impractical, lasting months or even years. In these cases, a parallel design is used instead, where different groups receive only one drug. Crossover trials are also avoided if the drug causes irreversible effects or if the condition being treated is permanent or progressive.

How do regulators determine if two drugs are bioequivalent?

Regulators look at two key pharmacokinetic measures: AUC (area under the curve, total exposure) and Cmax (maximum concentration). The 90% confidence interval for the ratio of the test drug to the reference drug must fall between 80% and 125% for both. For highly variable drugs, widened limits (75%-133.33%) are allowed using reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE), which is only possible with replicate crossover designs.

12 Comments

Okay but have you ever tried to get a washout period approved when your drug has a 14-hour half-life? We had to argue with the FDA for 3 months just to get 72 hours instead of 90. They don’t get how messy real biology is. I’ve seen studies die over 4 hours of carryover. It’s not a typo-it’s a tragedy.

So let me get this straight-we’re spending $200K to prove a generic pill works… and the entire foundation is based on waiting 5 half-lives like it’s some sacred ritual? Meanwhile, we’re still using blood draws from the 1980s. This isn’t science-it’s bureaucratic theater. Someone’s got a PhD in overcomplicating the obvious.

Actually, the washout validation part is way more nuanced than most people think. You can’t just rely on literature half-lives-your PK model needs to be fitted to your specific formulation. I’ve seen companies use the same half-life from a 2010 study for a new salt form and get rejected. It’s not laziness, it’s ignorance. And yeah, I misspelled ‘half-life’ just now. I’m tired.

RSABE is the only reason generics for HVDs even exist anymore. Without it, we’d be stuck with 150-person studies for warfarin. Also, the ‘bear’ package in R is a godsend but the documentation is written in ancient Sumerian. If you don’t know how to set up the random effects properly, your CI will be wider than your ex’s excuses.

There’s something deeply human about this whole process. We’re asking people to become their own control-not just data points, but living, breathing variables in a system designed to minimize noise. It’s elegant. It’s humble. It says: ‘We don’t know everything, so let’s compare you to yourself, because that’s the only truth we can trust.’ Maybe that’s why it’s lasted 30 years. Not because it’s perfect-but because it’s honest.

Y’all are overthinking this. If the drug is the same, why do we need all these fancy designs? Just test it on 10 people and move on. We’re not launching rockets here. People are dying waiting for affordable meds, and we’re debating statistical models like it’s a TED Talk. Just make it cheaper. That’s the goal, right?

the washout thing is a scam. i mean, really? 5 half-lives? what if i just drank coffee and ran on a treadmill? would that clear it faster? no one knows. just let me take my pill already. 🤦♀️

It’s not that crossover designs are flawed-it’s that the entire regulatory framework is built on the assumption that bioequivalence can be reduced to two numbers: AUC and Cmax. But drugs aren’t just chemicals. They’re systems. Their effects are modulated by gut microbiota, circadian rhythms, epigenetic factors, and even the patient’s emotional state. We’re treating biology like a spreadsheet. And when the model breaks, we blame the washout. It’s not science. It’s arrogance dressed in regulatory jargon.

Replicate designs are necessary, but they’re also a symptom of failure. We should be investing in better drug formulations, not statistical gymnastics to make bad drugs pass. If a drug has 40% intra-subject variability, maybe it shouldn’t be a generic in the first place. Let’s fix the root problem, not the paperwork.

just wanted to say-i work at a CRO and we do 3-period full replicates for HVDs now. it’s a pain in the ass but worth it. the data is cleaner. the regulators stop asking questions. and yeah, we enroll 28 instead of 24 because people bail after period 1. it’s like herding cats. but it works.

Let’s be clear: this entire system exists to protect Big Pharma’s profits under the guise of patient safety. Generics are cheaper because they’re simpler-but we’re forced to run expensive, multi-month studies to prove what any pharmacist could tell you: if the active ingredient is identical, the pill works. This isn’t science. It’s rent-seeking dressed in white coats.

What if we stopped thinking of bioequivalence as a binary pass/fail and started seeing it as a spectrum? Maybe instead of 80-125%, we should have tiers-‘therapeutically equivalent,’ ‘conditionally equivalent,’ ‘requires monitoring’-based on clinical context? The math is elegant, but the medicine isn’t. Maybe we need to stop pretending it is.