FAERS vs Sentinel Safety Monitoring Comparison Tool

Compare Safety Monitoring Approaches

This tool demonstrates key differences between traditional reporting (FAERS) and modern active surveillance (Sentinel Initiative) using real-world data examples from the article.

Risk Comparison Results

Click Calculate to view resultsNo calculation performed yet

No calculation performed yet

Note: FAERS shows only reported cases, while Sentinel analyzes actual population risk ratios. This demonstrates why Sentinel can detect signals that FAERS misses.

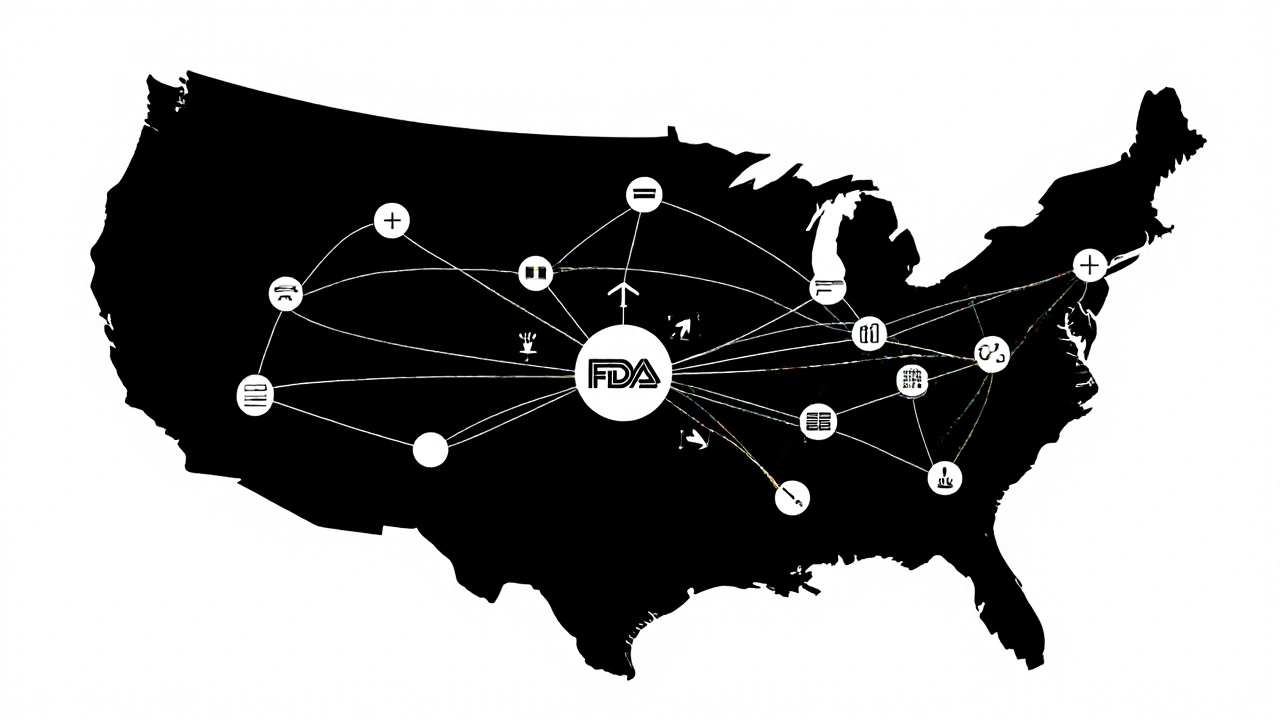

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration doesn’t wait for patients to get sick before acting. Since 2016, it’s been using FDA Sentinel Initiative-a massive, real-time data network-to catch dangerous side effects from drugs, vaccines, and medical devices before they become national crises. This isn’t just another database. It’s a distributed, nationwide surveillance system that analyzes health records from millions of Americans without ever moving their personal data. And it’s changing how we know if a medicine is truly safe after it hits the market.

Why Traditional Reporting Isn’t Enough

For decades, the FDA relied on the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS), where doctors, pharmacists, or patients voluntarily report side effects. Sounds simple, right? But here’s the problem: only about 1% to 10% of serious adverse events get reported. Many people don’t connect their symptoms to a drug. Others don’t know how to report. And even when they do, reports often lack details-no dosage, no medical history, no timeline. Without knowing how many people took the drug in the first place, it’s impossible to tell if a side effect is rare or common. Take a drug like rosiglitazone, used for diabetes. In 2007, concerns about heart risks emerged. But FAERS alone couldn’t confirm whether the risk was real or just noise. That’s when the FDA realized: passive reporting was like trying to spot a fire with a flashlight in a dark forest. You might see a spark, but you won’t see the whole blaze.How Sentinel Works: No Data Moved, All Insights Gained

The Sentinel Initiative solves this with a clever trick: it never takes your data. Instead, it asks the data to come to it. Sentinel connects to 18 major healthcare organizations-insurance companies, hospital systems, and clinics-that hold electronic health records and insurance claims for over 280 million people. These are called Data Partners. When the FDA wants to check if a drug increases the risk of kidney failure, they don’t download records. They send a secure, standardized query through a portal. Each Data Partner runs that same query on their own system. The results-aggregated, anonymized, and verified-are sent back to the FDA. All without moving a single patient record. This distributed model keeps data private, respects HIPAA, and avoids the legal nightmares of centralizing medical records. But it also means every partner must use the same tools and definitions. A “heart attack” in one system must match a “heart attack” in another. That’s why Sentinel uses a common data model called the Common Data Model (CDM). It turns messy, inconsistent EHRs into clean, comparable data.From Claims to Clinical Notes: The Rise of Real-World Evidence

Early on, Sentinel relied mostly on insurance claims data-things like diagnosis codes, prescriptions, and hospital visits. But claims data has gaps. It won’t tell you if a patient had a rash, dizziness, or memory loss unless it was billed as a separate visit. That’s why Sentinel started adding electronic health records (EHRs). These contain doctor’s notes, lab results, vital signs, and even free-text entries like “patient reports unusual fatigue after starting medication.” The Sentinel Innovation Center now uses natural language processing (NLP) to pull meaning from those unstructured notes. Machine learning models scan thousands of clinical summaries to find patterns humans might miss. In one 2021 study, Sentinel used EHR data to confirm that a common blood pressure drug increased the risk of angioedema-a dangerous swelling-in Black patients at higher rates than previously known. That finding led to updated safety labels within months.

What Sentinel Has Actually Found

Sentinel isn’t theoretical. It’s driven real regulatory actions:- Confirmed an increased risk of pancreatitis with GLP-1 agonists (weight-loss drugs like semaglutide)

- Detected a spike in Guillain-Barré syndrome after a specific flu vaccine, prompting a warning update

- Identified that certain diabetes drugs raised the risk of leg amputations in patients with poor circulation

- Helped validate the safety of mRNA vaccines in elderly populations during the pandemic

Who Uses Sentinel-and Why

It’s not just the FDA. Since 2019, Sentinel has been split into three centers:- Sentinel Operations Center (SOC): Runs the queries and manages the network

- Innovation Center (IC): Builds new tools using AI, machine learning, and causal inference models

- Community Building and Outreach Center: Trains researchers, industry partners, and international regulators to use the system

Limitations: Big Data Isn’t Perfect

Sentinel is powerful-but not magic. It still struggles with:- Rare events: If a side effect happens in 1 in 100,000 people, you need millions of records to spot it-and even then, noise can drown it out

- Data gaps: Not everyone visits a doctor. Home remedies, over-the-counter meds, or symptoms ignored by patients won’t show up

- Code errors: A misclassified diagnosis or incorrect billing code can lead to false signals

- Complexity: Running a query requires training in epidemiology, statistics, and health informatics. It’s not something a general practitioner can do on a lunch break

The Future: AI, Global Networks, and Real-Time Alerts

The next phase of Sentinel-sometimes called Sentinel 3.0-is already underway. With $304 million in funding, the FDA is pushing deeper into AI:- Using predictive models to flag drugs likely to cause problems before they’re even widely used

- Integrating wearable data (like heart rate monitors or glucose trackers) from patients who consent

- Building partnerships with the European Medicines Agency and Health Canada to create a global safety network

When you take a new medication, you’re trusting that someone is watching for hidden risks. The FDA Sentinel Initiative is that watcher. It’s not perfect. But it’s the most advanced, scalable, and secure system ever built to protect public health using real-world data.

How is Sentinel different from FAERS?

FAERS is a voluntary reporting system where people submit adverse event reports, often with incomplete or inconsistent data. Sentinel is an active surveillance system that analyzes real-world data from millions of electronic health records and insurance claims. It uses known exposure rates to calculate actual risk, not just counts of reports.

Does Sentinel collect personal health information?

No. Patient data stays with the healthcare organizations that own it. The FDA sends analytical queries to these organizations, and only aggregated, anonymized results are returned. No names, addresses, or identifiable details are ever shared with the FDA.

Can researchers outside the FDA use Sentinel?

Yes. Academics, industry scientists, and international regulators can submit research proposals through the Sentinel Innovation Center. If approved, they can run queries using the same tools and data as the FDA, under strict oversight and data use agreements.

How fast does Sentinel detect safety issues?

Typical safety assessments take 4 to 12 weeks, depending on complexity. This is much faster than traditional studies, which can take years. For urgent threats-like a spike in heart attacks after a new drug launch-Sentinel can deliver preliminary results in under two weeks.

Is Sentinel used outside the U.S.?

While the system is U.S.-based, its architecture and methods have inspired similar networks in Europe, Canada, Japan, and Australia. The FDA actively collaborates with international regulators to align data standards and share findings, making Sentinel a global model for drug safety monitoring.

8 Comments

Okay but let’s be real-this system sounds like Big Brother with a PhD 😅 I mean, they’re not collecting data… but they’re still watching EVERYTHING. My grandma took aspirin in 1998 and now some algorithm is deciding if it’s ‘associated’ with her knee pain? 🤔 I trust science, but I don’t trust the black box.

Also, why do I feel like this is just pharma’s way of saying ‘we’re transparent’ while quietly lobbying to keep the real data locked down? 🤫

They say ‘no data moved’… but who’s auditing the queries? Who’s stopping someone from reverse-engineering demographics from aggregated stats? I’ve seen how ‘anonymized’ data gets re-identified with just a zip code, birth date, and gender. This isn’t privacy-it’s theater. And the FDA? They’re not saints-they’re bureaucrats with better PR.

Also-sentinel ‘found’ that diabetes drugs cause amputations? Wow. Took them 15 years to notice? That’s not innovation-that’s negligence dressed up in AI.

And don’t even get me started on the ‘common data model’… if your EHR system can’t even spell ‘hypertension’ the same way twice, how are you gonna trust the math? 😒

Let me just say this: the fact that we’re even having this conversation is a victory. In 2005, we had no way of knowing if a drug was harming people until someone died-and even then, it took years to connect the dots. Now? We have a system that can detect signals across hundreds of millions of records in weeks.

Yes, it’s imperfect. Yes, there are gaps. But this is the closest we’ve ever come to a living, breathing public health immune system. We don’t need perfection-we need progress. And this? This is progress with teeth.

Also, the integration of clinical notes via NLP? That’s not just smart-that’s revolutionary. We’re finally moving from billing codes to actual human experience.

Don’t let cynicism blind you to the fact that this system saves lives every single day.

And yes-I’m aware this sounds like a TED Talk. But someone has to say it.

so the usa is spending millions to watch people’s medical records… but canada and europe just copy it? lol. we’re the tech leader, but everyone else gets to ride our coattails. classic.

also, why do we even need this? if you take a drug and get sick, go to the doctor. stop making computers do your job. also, i heard the nlp models are trained on biased data-so black people get flagged for side effects more even if they’re not at higher risk. just sayin’. america’s algorithm is racist.

Sentinel’s architecture is fundamentally flawed due to latent confounding in claims data. The CDM standardizes nomenclature but not phenotypic expression. NLP on EHRs introduces annotation bias. You cannot infer causality from observational data without counterfactual modeling. This is epidemiological sophistry wrapped in machine learning glitter.

Also, 280M records ≠ statistical power for rare events. You need 10^9 to detect 1:100k signals with 80% power. This is a toy system for regulatory theater.

Oh wow, so the government is now your personal medical stalker-using AI to predict your side effects before you even feel them? How… convenient. But let’s not pretend this isn’t surveillance capitalism with a white coat. They’re not protecting you-they’re profiling you. Your blood pressure, your glucose, your depression scores-all fed into a corporate-government algorithm that decides what’s ‘normal’ for your race, age, and zip code.

And don’t tell me ‘it’s anonymized.’ Anonymity is a myth. I’ve seen how they triangulate identities from prescription patterns and insurance claims. You think your grandma’s diabetes meds are safe? Maybe. But the algorithm knows she’s poor, lives in a food desert, and takes 12 pills a day. That’s not safety-it’s a risk score.

And who’s to say the next ‘signal’ isn’t just a statistical ghost? A glitch in the code that says ‘Black women over 50 are 3x more likely to die from coffee.’ And then? Suddenly, coffee gets flagged. And you? You’re not a person anymore. You’re a data point in a spreadsheet that never sleeps.

They call it innovation. I call it control.

And the worst part? You’re all nodding along like this is progress. But it’s just the next step in your own digital enslavement. Wake up.

And yes-I’ve read the white papers. I’ve seen the source code. You haven’t.

I just think it's cool that we can find out if a drug is dangerous faster now. Like, before, people had to wait years and sometimes people died before anyone did anything. Now they can catch it quicker. Not perfect but better. I'm glad someone's watching.

Also the part about EHR notes and fatigue-that's actually kind of beautiful. Doctors write stuff down and now computers can read it and help. That's kind of magic.

Thank you for sharing this comprehensive overview. The Sentinel Initiative represents a paradigm shift in pharmacovigilance-one grounded in ethical data stewardship, technical rigor, and public accountability. While challenges remain-particularly regarding data completeness and algorithmic transparency-the framework’s distributed architecture ensures that patient autonomy is preserved even as public health is enhanced.

It is worth noting that the integration of real-world evidence into regulatory decision-making is not merely a technological advancement, but a moral imperative. The lives saved through early detection of angioedema risk, pancreatitis signals, and vaccine-related complications are not abstract statistics-they are individuals who will live longer, healthier lives because of this system.

To those who express skepticism: your concerns are valid. But they must be addressed through engagement, not dismissal. The FDA has opened pathways for external researchers to contribute. That is not control-it is collaboration.

This is not the end of the journey. It is the beginning of a global learning health system. And we are all stakeholders in its success.