A kidney transplant isn’t just a surgery-it’s a second chance at life. For someone with end-stage renal disease (ESRD), where the kidneys have lost 85% or more of their function, dialysis keeps you alive, but it doesn’t restore your quality of life. A transplant can change that. People who get a kidney transplant live longer, feel better, and often return to work, travel, and even exercise again. But it’s not simple. There are strict rules about who qualifies, a complex operation to get through, and a lifetime of care afterward. If you or someone you love is considering this path, here’s what you really need to know.

Who Can Get a Kidney Transplant?

- You must have end-stage renal disease-meaning your kidneys are working at 15% or less of normal capacity. This is measured by your glomerular filtration rate (GFR), which should be 20 mL/min or lower. Some centers may consider you if your GFR is up to 25 mL/min, especially if your kidney function is dropping fast or you have a living donor ready.

- You need to be healthy enough for major surgery. That means your heart and lungs can handle it. If you have severe pulmonary hypertension-systolic pressure above 50 mm Hg-you’re typically not eligible. If you’re on long-term oxygen because of COPD, that’s also a disqualifier.

- Your body mass index (BMI) matters. A BMI over 35 is seen as risky. Over 45, and most centers won’t move forward. Obesity increases surgical risks by 35% and raises the chance of the new kidney failing by 20%.

- You can’t have active cancer. If you’ve had cancer, you usually need to be in remission for at least two to five years, depending on the type. Skin cancer or early-stage breast cancer might be okay after treatment. But aggressive cancers like untreated lung or liver cancer? Not a candidate.

- You must be free of active infections. HIV isn’t automatically a barrier anymore-if your viral load is undetectable and your CD4 count is above 200, you can qualify. Same with hepatitis B: if it’s controlled with medication, you may still be eligible.

- Mental health and substance use are evaluated. If you’re actively using alcohol or drugs, you’ll need to show at least six months of sobriety and proof of ongoing support. Severe untreated depression or psychosis that makes it hard to follow complex medication schedules can also disqualify you.

- You need a strong support system. Most transplant centers require you to have someone who can help you take your pills, drive you to appointments, and notice if something’s wrong. This isn’t optional-it’s critical.

Age alone doesn’t disqualify you. Some centers won’t transplant people over 75, but others look at fitness, not birth year. A 78-year-old who walks daily, manages their blood pressure, and has no heart issues may be a better candidate than a 55-year-old with diabetes and heart disease.

What Happens During the Surgery?

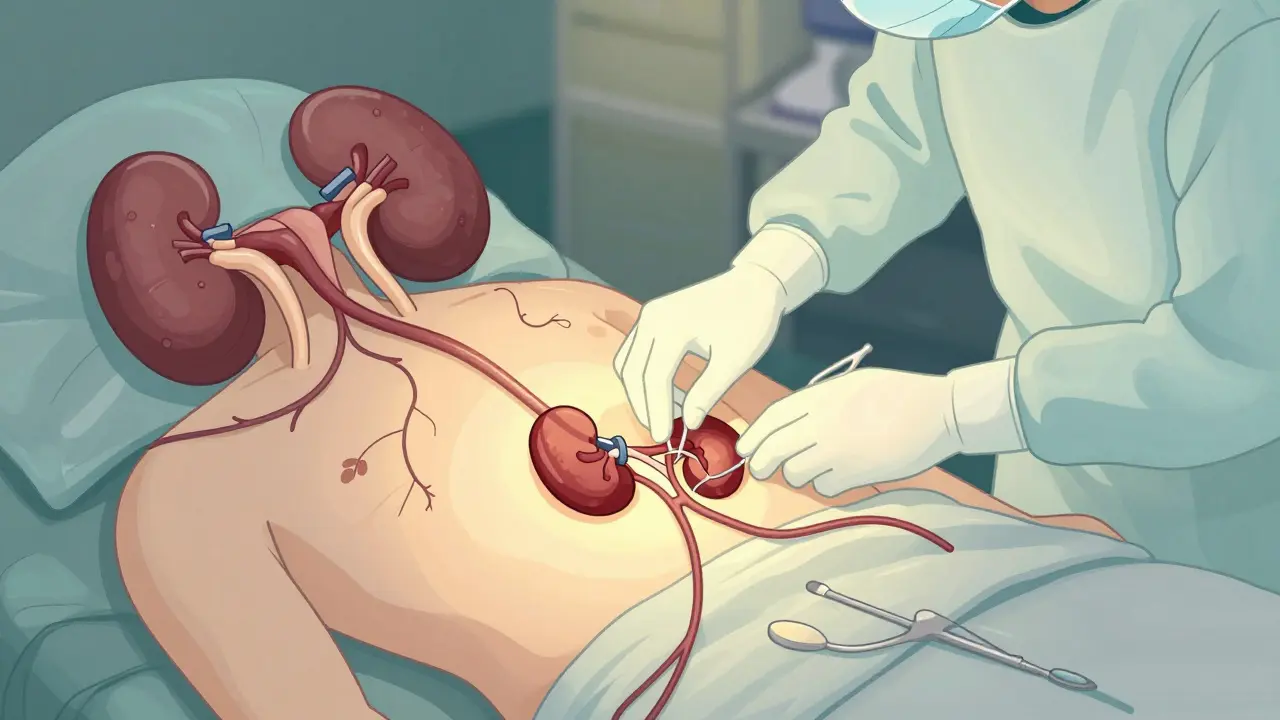

The surgery takes about three to four hours. You’re under general anesthesia, so you won’t feel anything. The surgeon places the new kidney in your lower abdomen, usually on the right or left side. The blood vessels of the new kidney are connected to your own blood supply-typically the iliac artery and vein. Then, the ureter (the tube that carries urine from the kidney to the bladder) is attached to your bladder.

Your original kidneys? They’re almost always left in place. Unless they’re causing infections, high blood pressure, or pain, there’s no reason to remove them. The new kidney starts working right away in most cases. In fact, you might see urine flowing into your bladder during surgery.

But not everyone gets lucky. About 20% of kidneys from deceased donors don’t start working immediately. This is called delayed graft function. It’s not rejection-it’s just the kidney needing a little more time to recover from the stress of donation and transport. During that time, you’ll need dialysis for a few days to a couple of weeks. It’s stressful, but it’s temporary.

Living donor transplants have a big advantage here. Because the kidney comes from a healthy person and is transplanted right after removal, it’s more likely to start working immediately. That’s one reason why living donor transplants have higher success rates.

What You’ll Need After Surgery

Here’s the hard truth: after a transplant, you’ll take anti-rejection drugs for the rest of your life. No exceptions. These medications stop your immune system from attacking the new kidney. But they also make you more vulnerable to infections and increase your risk of certain cancers.

The standard combo includes:

- A calcineurin inhibitor-usually tacrolimus or cyclosporine. These are powerful and require regular blood tests to keep levels just right.

- An antiproliferative agent-mycophenolate mofetil or azathioprine. These slow down immune cell growth.

- Corticosteroids-like prednisone. Often reduced over time, but many people stay on a low dose forever.

Some patients get induction therapy right after surgery-a one-time or short-term dose of antibodies to give the new kidney a better start.

Side effects are real. You might gain weight, get acne, develop high blood pressure, or have shaky hands. Some people get diabetes from the drugs. Bone thinning is common. That’s why you can’t just take the pills and forget about it. You need to see your transplant team regularly.

Here’s the typical follow-up schedule:

- Weekly for the first month

- Every two weeks for the next month

- Monthly for the next three to six months

- Every three months after that

- Once a year for life

Each visit includes blood tests to check kidney function, drug levels, and signs of infection. You’ll also get regular cancer screenings-skin checks, colonoscopies, and sometimes chest X-rays. Your doctor will monitor your bone density and cholesterol too.

How Long Do Transplants Last?

It’s not forever, but it’s long. About 95% of kidneys from living donors are still working after one year. After five years, 85% are still functioning. For kidneys from deceased donors, the numbers are slightly lower: 92% at one year, 78% at five years.

Why the difference? Living donor kidneys are healthier. They come from people who’ve been thoroughly screened. Deceased donor kidneys may have been exposed to trauma, low blood pressure, or longer cold storage times. Even so, both types offer far better survival than staying on dialysis.

On dialysis, only about half of patients survive five years. After a transplant, it’s 85%. That’s a massive difference.

Some transplants last 20 or even 30 years. Others fail sooner. The biggest causes of failure are chronic rejection (a slow, silent attack by the immune system), non-adherence to medication, or new health problems like diabetes or high blood pressure that damage the new kidney.

What’s New in Kidney Transplantation?

The field is moving fast. One big change is the Kidney Donor Profile Index (KDPI). This score, used since 2014, helps match kidneys with the longest expected life to the patients who need them most. A kidney with a low KDPI (under 20%) is considered excellent. A high-KDPI kidney (over 85%) might come from an older donor or someone with high blood pressure. But here’s the key: even a high-KDPI kidney is still better than dialysis.

Another breakthrough? Better organ preservation. New machines can keep kidneys alive and even repair them before transplant. This reduces delayed function and improves long-term outcomes.

And then there’s the holy grail: eliminating lifelong immunosuppression. Researchers at Stanford and the University of Minnesota are testing protocols that train the immune system to accept the new kidney without drugs. Early trials show promise-some patients have gone years without anti-rejection meds. If this works, it could change everything.

For now, though, the best option remains a living donor. A kidney from a healthy, matched living person gives you the highest chance of long-term success. If you have a friend or family member willing to donate, don’t hesitate to explore it. The process is safe for donors-most return to normal life within six weeks.

What If the Transplant Fails?

If your new kidney stops working, you go back to dialysis. That’s not a failure-it’s a reset. Many people get a second transplant. In fact, about 20% of transplant recipients get a second kidney. The wait is longer, and the risks are higher, but it’s still possible.

Some people choose to stay on dialysis instead of going back on the list. That’s a personal decision. But don’t assume your options are gone. Talk to your transplant team. They’ll help you weigh the risks and benefits.

Final Thoughts

A kidney transplant is one of the most effective treatments for end-stage kidney disease. It’s not easy. It requires discipline, support, and lifelong commitment. But for most people, the trade-off is worth it. You get back your energy, your freedom, and your future.

If you’re on the list, stay healthy. Watch your weight. Take your meds. Don’t skip appointments. If you’re considering donation, talk to your doctor. The need is huge-over 100,000 people in the U.S. alone are waiting. Every donor makes a difference.

Can you have a kidney transplant if you’re over 70?

Yes, age alone doesn’t disqualify you. Many centers evaluate older patients based on overall health, not just birth year. If you’re physically active, have no major heart or lung problems, and can manage medications, you may be a good candidate. Some transplant programs have successfully transplanted patients into their 80s.

What happens if I miss a dose of my anti-rejection medicine?

Missing even one dose can increase your risk of rejection. Anti-rejection drugs need to stay at a steady level in your blood. If you miss a dose, take it as soon as you remember-but don’t double up. Call your transplant team immediately. They may want to check your drug levels and adjust your schedule. Consistency is the #1 factor in long-term transplant success.

Can I drink alcohol after a kidney transplant?

Moderate alcohol is usually okay-about one drink per day for women, two for men. But heavy drinking can damage your new kidney and interfere with your medications. Alcohol also increases the risk of liver problems and high blood pressure. Always check with your doctor. Some centers advise complete abstinence, especially if you have a history of alcohol use disorder.

How long is the wait for a deceased donor kidney?

It varies by location, blood type, and how long you’ve been on the list. On average, you might wait three to five years in the U.S. People with common blood types (like O or A) often wait longer because there are more people waiting for those kidneys. Those with rare blood types (like AB) may wait less time. Having a living donor can cut your wait to zero.

Can I get pregnant after a kidney transplant?

Yes, many women have healthy pregnancies after a transplant. But it’s not recommended until at least one year after surgery, and only if your kidney function is stable and your medications are pregnancy-safe. You’ll need close monitoring by both your transplant team and an obstetrician. Some immunosuppressants, like mycophenolate, must be switched before conception because they can cause birth defects.

What foods should I avoid after a transplant?

Avoid grapefruit and pomegranate-they interfere with how your body processes anti-rejection drugs. Raw or undercooked meat, unpasteurized dairy, and raw sprouts increase infection risk, especially in the first few months. Limit salt and sugar to protect your blood pressure and blood sugar. Your dietitian will give you a personalized plan based on your medications and lab results.

If you’re considering a transplant, start by talking to your nephrologist. They can refer you to a transplant center for evaluation. Don’t wait until you’re desperate. The earlier you’re assessed, the better your chances of getting a transplant before you need dialysis.

15 Comments

Transplant isn't just medical-it's existential. You're not just getting a new organ, you're getting a new relationship with time, with your body, with mortality. The drugs don't just suppress immunity; they suppress the illusion of control. Every pill is a reminder: you're alive because of chemistry, not luck. And yet, here we are-people walking around with foreign tissue inside them, thriving, working, laughing. That's the quiet miracle no one talks about.

So let me get this straight-we’re giving people a second chance at life… but only if they’re thin enough, sober enough, and mentally stable enough to not screw it up? Sounds like the American Dream with a BMI requirement.

yo this is wild-i had no idea u could get a transplant with hiv now? my cousin’s on dialysis and he’s hiv+ and they told him no way. guess the med world’s catchin up. also, what’s this kdpi thing? sounds like some kinda crypto but i think it’s about kidney quality? lmk if i’m off base

They let in foreigners and drug addicts but won't let a real American who’s worked his whole life get a kidney? This is why our system’s broken. We’re giving organs to people who don’t even speak English while our veterans wait. Someone’s gotta draw the line-this ain’t charity, it’s a national resource!

OMG I just cried reading this 🥹 I have a friend who got a transplant last year and she’s back hiking in Colorado! Also, grapefruit is EVIL?? I LOVE grapefruit 😭

While the clinical data presented is largely accurate, I must emphasize that the sociopolitical implications of organ allocation remain under-examined in mainstream discourse. The commodification of biological material under neoliberal healthcare frameworks introduces ethical paradoxes that warrant interdisciplinary scrutiny.

Let’s be brutally honest-this whole system is a farce. You’re told you’re a candidate until they see your credit score. They don’t care if you’re dying-they care if you have insurance that covers the 100k co-pay they never told you about. And don’t get me started on the ‘support system’ requirement. What if you’re homeless? What if you’re alone? You just die quietly while bureaucrats check boxes. This isn’t medicine-it’s a lottery rigged for the privileged.

Biggest tip? Don’t skip your blood tests. I saw a guy lose his transplant because he thought ‘I feel fine’ meant ‘I’m good.’ Nope. Your meds need checking like your car’s oil. One missed visit and boom-your kidney starts fading. Stay on top of it.

People who abuse drugs or alcohol don’t deserve a second chance. Why should we give them a healthy kidney when they keep destroying their own bodies? This isn’t a reward system-it’s a sacred gift. It should go to the worthy.

Living donor transplants are the real hero story here. My neighbor donated to his sister-went back to coaching little league in 6 weeks. The fact that we can do this safely? That’s human ingenuity at its best. We need more awareness, not just about transplants, but about how simple it is to save a life.

just got my kidney transplant last year and wow-this article got it right. the meds are rough but i can finally sleep through the night. no more dialysis schedules, no more feeling like a ghost. also, i still drink coffee. no one told me i had to quit that lol

The KDPI metric is critical for equitable allocation. A high-KDPI kidney isn’t ‘low quality’-it’s contextually appropriate. For an elderly recipient with limited life expectancy, a kidney with 10-year expected function is optimal. We must move beyond the myth that only ‘perfect’ organs are viable. This is precision medicine in action.

When I was in India last year, I met a family where the son donated his kidney to his mother. No money changed hands. No hospital bureaucracy. Just love. We talk about tech and drugs, but the real breakthrough is still the human heart. We need more stories like that-not just stats.

Did you know the government is secretly harvesting organs from undocumented immigrants? They’re using the ‘transplant waitlist’ as cover. The ‘living donor’ thing? A distraction. They don’t want you to know how many kidneys come from ‘accidents’ that were never accidents. Google ‘Project Lazarus’ and see for yourself.

For those asking about drug interactions: tacrolimus levels are highly sensitive to CYP3A4 inhibitors. Grapefruit, azole antifungals, macrolides-all can cause toxic accumulation. Always consult your pharmacist before taking any OTC med, herb, or supplement. Even St. John’s Wort can trigger rejection. This isn’t scare tactics-it’s pharmacokinetics 101.