Every day, pharmacists dispense millions of generic medications-cheaper, FDA-approved copies of brand-name drugs. For most people, they work just as well. But not always. When a patient starts a new generic and suddenly feels worse, gets new side effects, or sees their condition slip out of control, it’s not just bad luck. It could be a problematic generic.

Why Generic Drugs Aren’t Always Interchangeable

Generic drugs must contain the same active ingredient, dose, and route as the brand-name version. That’s the law. The FDA says they’re bioequivalent-meaning they deliver the same amount of drug into the bloodstream within an 80-125% range of the original. Sounds fine, right? But here’s the catch: that 45% window is wide. For some drugs, even a 20% drop in absorption can mean the difference between control and crisis. Take levothyroxine, used for hypothyroidism. A patient stabilized on one generic manufacturer might switch to another-and their TSH level jumps from 2.1 to 8.7 in six weeks. That’s not a fluke. It’s a documented pattern. The FDA has flagged this repeatedly. Why? Because small differences in inactive ingredients, tablet coating, or dissolution rates can alter how slowly or quickly the drug releases. For thyroid meds, even tiny shifts in hormone levels can cause fatigue, weight gain, or heart rhythm problems. The same goes for warfarin, phenytoin, and digoxin. These are narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs. Their safe and effective dose range is razor-thin. A little too much? Risk of bleeding or seizures. A little too little? Clots or seizures. Studies show patients on NTI generics who switch manufacturers are 2.3 times more likely to experience therapeutic failure. And it’s not rare: 18 drugs are officially listed by the FDA as NTI. Pharmacists need to treat these like precision tools, not commodities.When a Generic Just Doesn’t Work

You’d think if a drug is approved, it works. But approval doesn’t guarantee consistent performance. The FDA’s Orange Book lists therapeutic equivalence codes. “AB” means it’s approved as equivalent. “BX” means it’s not-often because bioequivalence data is incomplete or conflicting. Many pharmacists don’t check this. They should. Here’s what to watch for:- A patient reports their medication “doesn’t feel the same” after a switch-even if they can’t explain why.

- Therapeutic drug monitoring shows a sudden, unexplained shift in blood levels (like digoxin or tacrolimus).

- Side effects appear or worsen after switching manufacturers, especially GI upset, dizziness, or rash.

- The patient’s condition regresses: blood pressure rises, seizures return, cholesterol spikes.

Look-Alike, Sound-Alike: The Silent Killer

Another major issue isn’t chemistry-it’s confusion. The Institute for Safe Medication Practices says 14.3% of generic medication errors come from look-alike or sound-alike names. Oxycodone/acetaminophen vs. hydrocodone/acetaminophen. Clonazepam vs. clonidine. Alprazolam vs. amitriptyline. These aren’t typos. They’re dangerous mix-ups. Pharmacists must double-check the manufacturer and strength when dispensing. Don’t assume the label is right. If a patient says, “I’ve never had this pill before,” pay attention. The pill imprint, color, or shape might be different. That’s a red flag. Document the manufacturer every time. If something goes wrong later, you’ll need that info to trace it back.

Complex Generics: Where the System Breaks Down

Not all generics are created equal. Simple pills? Usually fine. But complex formulations-inhaled steroids, topical creams, injectables, or extended-release tablets-are harder to copy. The FDA found that 7.2% of generic extended-release opioids failed dissolution testing in 2020. Only 1.1% of immediate-release versions did. Why? Because replicating the slow-release mechanism requires advanced tech and precise manufacturing. These products make up only 1.2% of generic approvals-but 27% of the brand-name market. That’s a gap. And it’s growing. In 2023, 47 of the 123 drug shortages in the U.S. were due to quality issues at generic manufacturing plants, mostly overseas. India and China supply most of the world’s generics. The FDA inspected 387 facilities there in 2022 and found over 1,200 quality issues. That’s not just a supply chain problem. It’s a safety risk.What Pharmacists Should Do

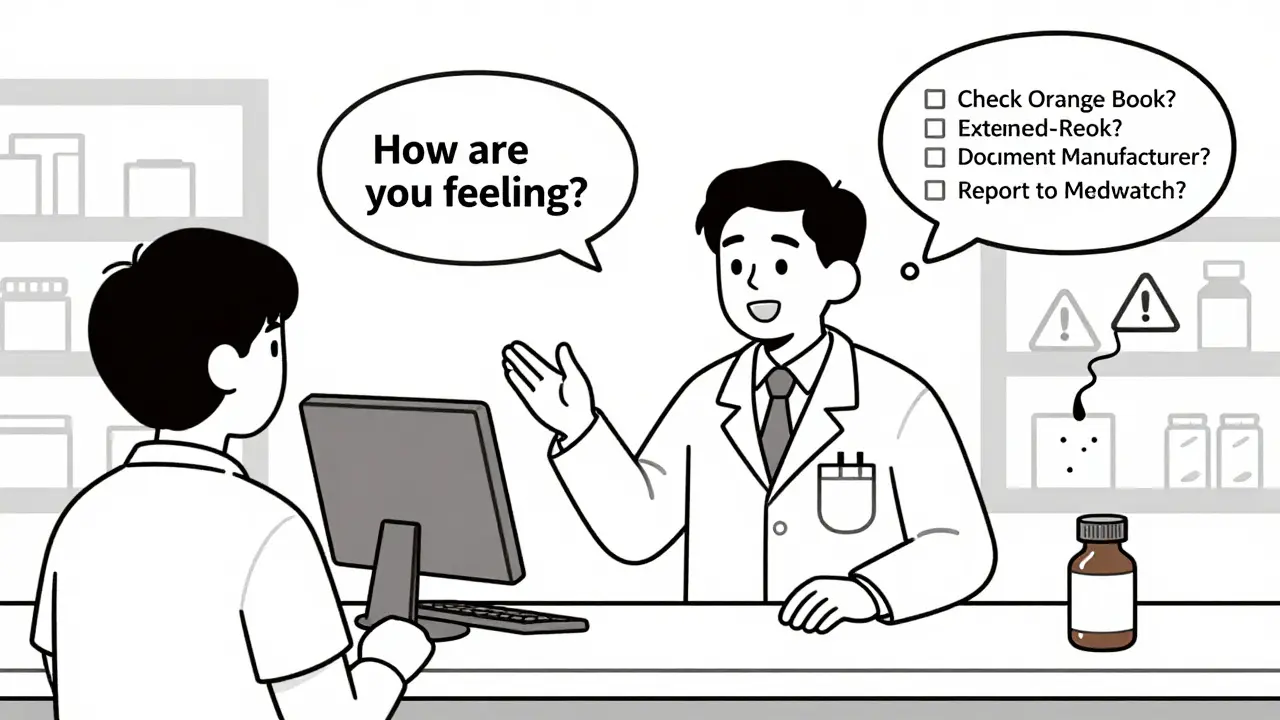

You don’t need to be a scientist to spot trouble. You need to be observant and proactive.- Check the Orange Book. Before dispensing, confirm the generic is rated “AB” for NTI drugs. If it’s “BX,” don’t substitute without consulting the prescriber.

- Document the manufacturer. Write it on the prescription label or in the system. If a patient reports an issue, you’ll know exactly which batch to trace.

- Ask patients directly. After a switch, call or message: “How are you feeling on the new pill?” Don’t wait for them to complain.

- Report it. Use the FDA’s MedWatch system. One report won’t change much. But 100? That triggers an investigation. Pharmacist reports increased by 18.3% in states with mandatory reporting.

- Don’t assume cost equals safety. The cheapest generic isn’t always the best. If a patient does better on a slightly more expensive version, advocate for it. Insurance can often be appealed.

It’s Not About Being Anti-Generic

Let’s be clear: generics save lives by making medicine affordable. Ninety percent of prescriptions in the U.S. are filled with generics. They’ve cut drug spending by billions. But that doesn’t mean we should ignore the risks. The goal isn’t to stop generics. It’s to make them safer. The FDA is trying. They’ve launched new programs to test more samples, speed up reviews for complex drugs, and use AI to detect patterns in adverse events. But frontline detection still falls to you. Patients trust you. They assume the pill they get today is the same as yesterday. When it’s not, you’re the one who can catch it before someone gets hurt.What Patients Need to Know

Patients don’t need to understand bioequivalence. But they should know this: if you switch generics and feel different, speak up. Don’t assume it’s “all in your head.” Take notes: when did the change happen? What symptoms started? Did your blood work change? Bring that to your pharmacist. And if your pharmacist says, “It’s the same drug,” ask: “Which manufacturer is this?” Then ask: “Is this rated AB in the Orange Book?” If they don’t know, find someone who does.Final Thought

Generic drugs are a triumph of public policy. But like any system, they can be abused, mismanaged, or misunderstood. The science says they’re mostly safe. The data says a small but significant number aren’t. Your job isn’t to question every generic. It’s to know when to pause, investigate, and act. The next time a patient says, “This one doesn’t work like the last,” don’t brush it off. You might just stop a hospitalization-or worse.Are all generic drugs safe?

Most are. Over 90% of prescriptions in the U.S. are generics, and the vast majority work just like brand-name drugs. But not all. Some have inconsistent dissolution rates, poor quality control, or bioequivalence issues-especially complex formulations like extended-release tablets, inhalers, or NTI drugs. The FDA approves them based on standards, but post-market data shows some batches fail in real-world use.

Which generic drugs are most likely to cause problems?

Narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs are the highest risk: levothyroxine, warfarin, phenytoin, digoxin, and tacrolimus. These have very little room for error-small changes in absorption can lead to serious harm. Extended-release formulations, especially for opioids or heart medications, also show higher failure rates. Look-alike/sound-alike names like oxycodone/acetaminophen and hydrocodone/acetaminophen cause frequent dispensing errors.

How do I know if a generic is therapeutically equivalent?

Use the FDA’s Orange Book. Look up the brand-name drug and check its generic equivalents. If it’s rated “AB,” it’s considered therapeutically equivalent. If it’s “BX,” it’s not-either because bioequivalence hasn’t been proven or there are unresolved issues. Always verify this before substituting, especially for NTI drugs.

Should I always stick with the same generic manufacturer?

For most drugs, switching is fine. But for NTI drugs or complex formulations, consistency matters. If a patient is stable on a specific brand, it’s safer to keep them on it. Document the manufacturer each time. If a patient reports problems after a switch, revert to the original and report it. Don’t assume the new one is identical just because it’s the same active ingredient.

What should I do if a patient has a bad reaction to a generic?

First, confirm the switch happened recently-within 2-4 weeks. Check their lab values if applicable (like TSH for thyroid meds or INR for warfarin). Document the manufacturer, lot number, and symptoms. Contact the prescriber to discuss alternatives. Then file a report with the FDA’s MedWatch system. One report may not change much, but aggregated data triggers investigations and recalls.

15 Comments

They let Chinese factories make our meds and wonder why people die.

It’s not a coincidence. It’s policy.

My aunt died after switching generics. They told her it was 'just anxiety'.

The pill looked different. The script was fine.

They never checked the manufacturer.

Now I refuse all generics unless I hold the bottle and read the imprint.

They’re not drugs. They’re lottery tickets.

Let’s be clear: the FDA’s 80-125% bioequivalence window is a regulatory abomination.

For NTI drugs like warfarin, this isn’t 'margin of error'-it’s therapeutic negligence.

Pharmacists who don’t cross-reference the Orange Book are committing malpractice by omission.

And don’t get me started on the lack of post-market surveillance for complex formulations.

This isn’t about 'cost savings'-it’s about systemic failure disguised as efficiency.

I’ve been a pharmacist for 22 years.

I’ve seen this happen too many times.

Patients come in saying 'it’s not working like before'-and we just shrug.

We’re trained to trust the system.

But the system is broken.

And we’re the ones who pay the price when things go wrong.

Not the manufacturers.

Not the regulators.

Us.

Good post. Seriously. This needs more attention.

Here’s what I do: I keep a little log in my system-manufacturer, lot#, patient note.

For NTI meds, I even print out the Orange Book rating and give it to the patient.

Most don’t care. But the ones who do? They become advocates.

And that’s how change starts.

One patient. One pill. One report at a time.

Just had a patient tell me her blood pressure spiked after switching to a new generic lisinopril.

I checked the Orange Book-AB rating.

But the pill looked different.

So I called the manufacturer.

Turns out the coating changed and it dissolved too fast.

She’s back on the old one now.

And I’m documenting every single switch from now on.

Because I can’t afford to be wrong.

Neither can they.

Everyone’s blaming the generics.

But the real problem? The FDA.

They approve drugs based on outdated methods.

They don’t test real-world absorption.

They don’t audit foreign factories properly.

And they let pharmacists be the last line of defense.

That’s not oversight. That’s negligence.

And you’re all just complicit by not screaming louder.

Hey, I get it. We want cheap meds.

But here’s the thing: cheap shouldn’t mean dangerous.

I’ve had patients cry because their seizure meds stopped working after a switch.

They thought they were being 'smart' by saving money.

Turns out, they were risking their lives.

So now I tell them: 'If your body feels different, it’s not in your head. It’s in the pill.'

And I fight insurance for the right brand.

Because sometimes, safety costs more.

And that’s okay.

Just got off the phone with my mom.

She’s on levothyroxine.

Switched generics last month.

Now she’s exhausted, gaining weight, and crying for no reason.

I checked the Orange Book-AB.

But the pill is a different color.

So I called her pharmacy.

They said, 'It’s the same drug.' 😒

Well, it’s not the same drug if it’s making her feel like a zombie.

Time to switch pharmacies.

And file a MedWatch report.

Because someone needs to care.

And it’s not going to be them. 🤦♀️💊

What if the real issue isn’t the generic? What if it’s the patient’s belief that the pill changed?

Placebo effect works both ways.

What if the anxiety of switching is what’s making them feel worse?

Maybe we’re pathologizing normal adaptation.

Maybe we’re giving power to the pill instead of the person.

Just a thought.

I used to think generics were all the same.

Then my dad had a stroke after switching his generic clopidogrel.

Turns out, the new version had a different filler that affected absorption.

He’s fine now-on the original brand.

But I’ll never trust a random pill again.

Now I ask for the manufacturer every time.

And I write it down.

Because if my dad’s life isn’t worth the extra $3, what is?

China makes our meds. That’s why.

Thank you for writing this.

It’s so easy to feel powerless when you’re just trying to get your meds.

But you’re right-we can be the change.

I’ve started keeping a little notebook: 'Medication Log'-date, manufacturer, how I felt.

It’s tiny.

But it’s mine.

And when I go to the pharmacy, I show it.

They don’t always listen.

But sometimes... they do.

And that’s enough for now.

❤️

Of course generics are dangerous.

Why do you think Big Pharma pushes them?

They own the generic companies.

They control the FDA.

They want you dependent on cheap, unreliable pills so you never question the system.

Wake up.

This isn’t medicine.

This is control.

Let me tell you about the time I got a generic version of my dad’s digoxin.

He started hallucinating.

Thought he saw his dead wife in the corner.

We called the pharmacy.

They said, 'It’s the same drug.'

Turns out, the new one had 30% higher bioavailability.

He was nearly dead.

They didn’t even test it.

And now? They still sell it.

That’s not a system.

That’s a death sentence with a barcode.