When you pick up a prescription and see a different name on the bottle - maybe it’s no longer "Lipitor" but "atorvastatin" - you might wonder: is this the same thing? Will it work the same? Will it hurt me? These aren’t silly questions. They’re the kind that keep doctors, pharmacists, and regulators up at night. And the answer lies in something called bioequivalence.

What Bioequivalence Really Means

Bioequivalence isn’t marketing jargon. It’s a hard, scientific standard. It means two versions of the same drug - one brand-name, one generic - deliver the exact same amount of active ingredient into your bloodstream at the same speed. Not close. Not "pretty much." Exactly.

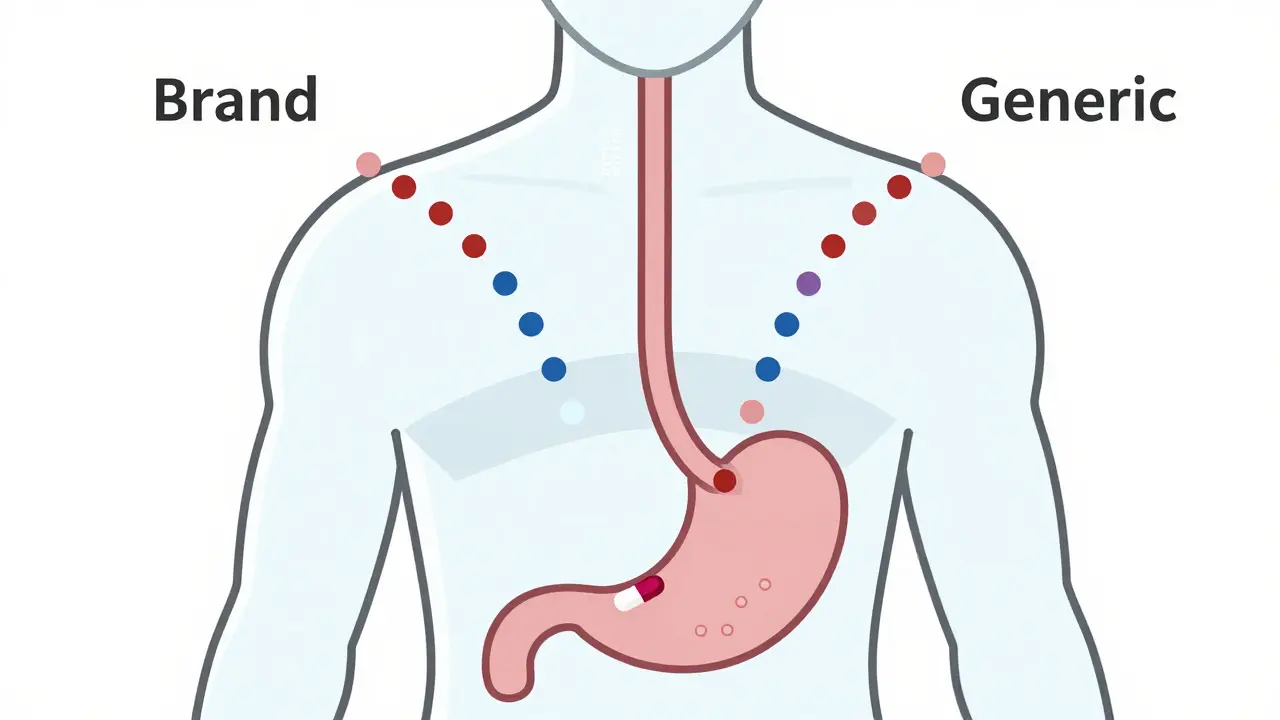

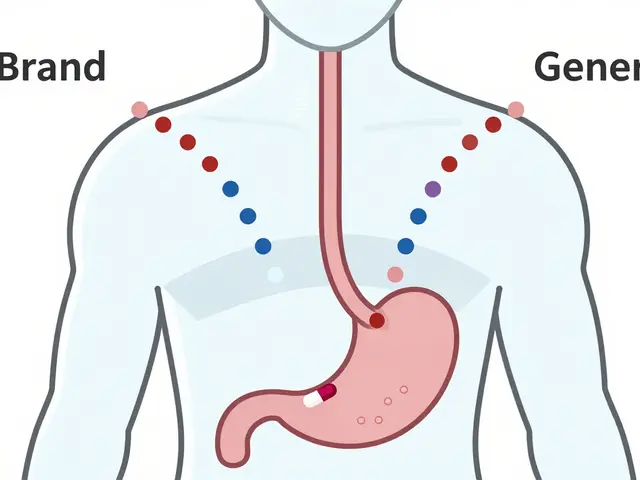

Here’s how it works: when you swallow a pill, your body absorbs the drug. That absorption happens in your gut, then travels through your liver, and finally enters your blood. The key measurements are AUC (how much drug gets into your system over time) and Cmax (how high the peak concentration gets). For a generic drug to be approved, its AUC and Cmax must fall within 80% to 125% of the brand-name version. That’s not a guess. It’s a statistically proven range based on thousands of studies.

Why this range? Because your body naturally varies. One day you’re well-rested, another you’re stressed. Your stomach might be full or empty. The 80-125% window accounts for that normal biological noise. If a generic drug stayed outside this range, it could be too weak - meaning your condition doesn’t improve - or too strong - raising your risk of side effects.

Why This Matters for Your Health

Imagine you’re on warfarin, a blood thinner. Too little, and you could clot. Too much, and you could bleed internally. That’s a narrow therapeutic index drug - meaning the difference between working and being dangerous is tiny. For drugs like this, regulators tighten the bioequivalence rules to 90-111%. Why? Because even a 10% shift in blood levels can change your risk of stroke or hemorrhage.

Or take levothyroxine, used for hypothyroidism. In 2012, the FDA cracked down after reports of patients switching generics and experiencing fatigue, weight gain, or heart palpitations. The problem wasn’t the drugs being unsafe - it was inconsistent absorption between batches. The FDA responded by requiring stricter bioequivalence testing. Since then, patient reports have stabilized. A 2022 survey found 58% of users said generic levothyroxine worked just like the brand. That’s not luck. That’s science working.

Now think about sertraline, an antidepressant. Some patients on Reddit reported mood swings after switching to a generic version. Sounds scary, right? But here’s the data: the FDA’s adverse event database shows only 0.07% of all reported drug problems involved generics with confirmed bioequivalence. Meanwhile, brand-name drugs accounted for 2.3%. That’s 30 times higher. Why? Because brand-name drugs are used by fewer people. When millions take a generic, even rare side effects get noticed. But if the drug meets bioequivalence standards, those events are random - not caused by the drug itself.

How Testing Is Done - And Why It’s Not Simple

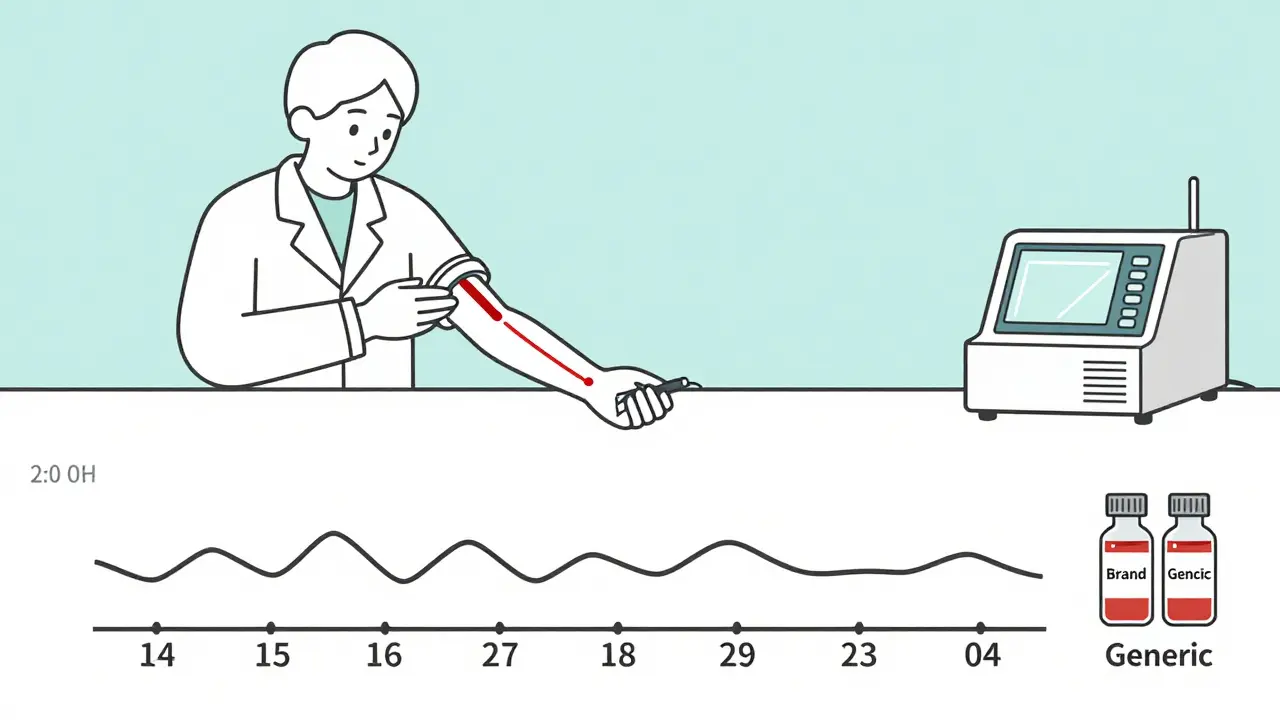

Bioequivalence isn’t tested on patients. It’s tested on healthy volunteers. Why? Because you don’t want to risk someone’s health while checking if a pill works. Volunteers take one version, then after a washout period, the other. Blood is drawn every 15-30 minutes for 24-72 hours. Labs use ultra-sensitive machines - LC-MS/MS - to measure drug levels down to billionths of a gram.

It’s expensive. A single study costs $1-2 million. It takes 12-18 months. And it’s not just about swallowing a pill. If the drug is meant to be taken with food, the study must be done both fasting and fed. That’s because food can change how fast the drug gets absorbed. In Japan, they only test fasting, even if the brand is taken with meals - because their regulators believe the data is still valid if concentrations are measurable. In the U.S., they require both. That’s why a generic made for Europe might not be approved in the U.S. - the testing rules differ.

And then there are complex drugs. Creams, inhalers, eye drops. These don’t go into your bloodstream the same way pills do. For them, measuring blood levels doesn’t tell you if the drug is working in the skin or lungs. So regulators are now using new tools: in-vitro tests that mimic skin layers, or imaging that tracks where the drug goes in the body. The FDA’s 2022 initiative on complex generics is trying to catch up - because if the drug doesn’t reach the right place, bioequivalence means nothing.

Who’s Watching? And Is It Enough?

The FDA, EMA, Health Canada, Medsafe (New Zealand), and WHO all require bioequivalence testing. In 2023, 134 countries had formal rules - up from 89 in 2015. That’s global recognition: this isn’t a U.S. thing. It’s a safety thing.

But it’s not perfect. Experts like Dr. Kenneth Falci warn that for drugs with very narrow windows - like digoxin or phenytoin - even the tightened 90-111% range might not be enough. Some generics pass the test but still cause problems in real life. Why? Because the test doesn’t capture every patient’s biology. One person might metabolize the drug slower. Another might have gut inflammation that slows absorption. Bioequivalence doesn’t guarantee identical results for everyone - but it guarantees the drug behaves the same way in most people.

That’s why pharmacists are trained to watch for changes after a switch. If you’re on a critical drug and start feeling off, tell your doctor. Don’t assume it’s "just in your head." But also don’t assume the generic is broken. Most of the time, it’s not.

The Bigger Picture: Safety, Cost, and Access

Without bioequivalence testing, generic drugs wouldn’t exist. Or they’d be a gamble. And that’s not just about money - it’s about access. In the U.S., generics make up 90% of prescriptions but only 23% of drug spending. In 2020, they saved the system $313 billion. In New Zealand, where public health funding is tight, generics let the government treat more people without raising taxes.

For someone on dialysis, a $500 monthly brand-name drug becomes $30 with a generic. That’s the difference between staying on treatment and quitting. Bioequivalence testing makes that possible - safely.

And the system keeps improving. The FDA now accepts computer models (PBPK) to predict how a drug behaves, reducing the need for human studies. AI is being trained to predict bioequivalence from dissolution profiles. The goal? Faster approvals, fewer trials, and still the same safety.

What You Should Know as a Patient

You don’t need to understand chromatography or geometric mean ratios. But you do need to know this:

- Generic drugs are not "cheap copies." They’re legally required to be the same.

- If you’ve had no issues with the brand, switching to a generic is safe - unless your doctor says otherwise.

- If you feel different after a switch, don’t ignore it. Talk to your pharmacist or doctor. But don’t automatically blame the generic.

- For critical drugs (blood thinners, thyroid meds, seizure meds), stick with the same brand or generic unless your provider approves a change.

- Check the FDA’s Orange Book or your country’s drug register. It lists which generics are approved as bioequivalent.

Generic drugs aren’t perfect. But the system that checks them - bioequivalence testing - is one of the most rigorously enforced safety nets in modern medicine. It’s not flashy. It doesn’t make headlines. But every time you refill a prescription and pay less, it’s because someone ran a test to make sure you wouldn’t pay with your health.

Are generic drugs as safe as brand-name drugs?

Yes - if they’ve passed bioequivalence testing. Regulatory agencies like the FDA and EMA require generics to prove they deliver the same amount of active ingredient at the same rate as the brand. Once that’s shown, and the manufacturing quality is verified, the generic is approved as equally safe and effective. Adverse event data shows generic drugs with confirmed bioequivalence are involved in far fewer safety reports than brand-name drugs, not because they’re safer, but because they’re used more widely - and the system catches real problems.

Why do some people say generics don’t work for them?

Sometimes, it’s not the drug - it’s the switch. If you’ve been on a brand for years, your body adapts. Switching to a generic - even one that meets all scientific standards - can feel different. That doesn’t mean it’s ineffective. It might be your body adjusting. But if symptoms persist - like mood changes, dizziness, or worsening symptoms - talk to your doctor. For narrow therapeutic index drugs (like warfarin or levothyroxine), small differences in absorption can matter. In those cases, your provider might recommend staying on the same version.

Is bioequivalence testing the same everywhere?

No. While most countries follow the 80-125% range, details vary. The U.S. often requires both fasting and fed studies. Japan only tests fasting. For complex drugs like inhalers or creams, methods differ even more. The World Health Organization and international regulators are working to harmonize rules, but differences still exist. That’s why a generic approved in Europe might not be sold in the U.S. - the testing requirements don’t match.

What are narrow therapeutic index drugs, and why are they special?

These are drugs where the difference between a helpful dose and a dangerous one is very small. Examples include warfarin, digoxin, phenytoin, and levothyroxine. For these, regulators tighten bioequivalence limits to 90-111% instead of 80-125%. Some experts argue even that’s not enough, especially for drugs with high variability. That’s why pharmacists often recommend sticking with the same generic or brand - consistency matters more than cost savings here.

How do regulators ensure generic drugs are made safely?

Bioequivalence testing only proves the drug works the same. Manufacturing quality is checked separately. Regulators inspect factories - sometimes unannounced - to ensure they follow Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP). A drug can pass bioequivalence but still be rejected if the factory has contamination issues, inconsistent tablet weights, or poor packaging. The FDA and EMA both publish inspection reports, and many countries share inspection data to avoid duplication.

Can I trust a generic drug from another country?

Only if it’s approved by your country’s regulator. Many countries import generics from India or China. But unless those products are officially approved by your national health authority (like Medsafe in New Zealand or the FDA in the U.S.), they haven’t been tested under your country’s standards. Buying unapproved generics online is risky - you might get a fake, expired, or mislabeled product. Always get your meds from a licensed pharmacy.

Does bioequivalence testing apply to biosimilars?

No. Biosimilars are not the same as generic drugs. Generics are exact chemical copies of small-molecule drugs. Biosimilars are copies of large, complex biological drugs - like insulin or cancer antibodies. Because they’re made from living cells, they can’t be identical. So instead of bioequivalence, regulators use a "totality of evidence" approach: comparing structure, function, immune response, and clinical outcomes. The standards are stricter and more complex - but the goal is the same: patient safety.

12 Comments

So let me get this right-you’re telling me that a pill made in a factory in India, with ingredients sourced from three different continents, and packaged by someone who probably doesn’t speak English, is literally the same as the one I paid $200 for last year? And you want me to believe that because some math between 80% and 125% lines up, my anxiety won’t spiral when I switch? I’m not scared of science-I’m scared of the people who think math is a substitute for human experience.

I’ve been on levothyroxine for 12 years, switched generics three times, and never had an issue-but I always check the pill color and shape first. If it looks different, I ask the pharmacist. It’s not paranoia, it’s habit. And honestly? The savings are insane. I used to skip doses because of cost. Now I take them like clockwork. That’s worth more than any brand-name placebo effect.

Let’s be brutally honest: bioequivalence is a regulatory farce. The 80-125% window is a statistical sleight-of-hand designed to appease pharmaceutical conglomerates. The fact that the FDA allows this for drugs like phenytoin-where a 5% deviation can cause seizures-is criminal negligence. And don’t get me started on how Indian manufacturers game dissolution profiles by altering excipients. The system is rigged. You think you’re saving money? You’re subsidizing corporate fraud.

Y’all are overcomplicating this. If your doctor says it’s safe, trust them. If you feel weird after switching, tell them. Simple. I’m a nurse, and I’ve seen people panic over a pill that looks different-and then realize their thyroid levels were perfectly stable. Stop listening to Reddit horror stories. Your body isn’t a magic box-it’s biology. And biology loves consistency, not fear.

It is imperative to underscore that the bioequivalence thresholds established by regulatory agencies are not arbitrary; they are grounded in pharmacokinetic principles derived from rigorous statistical analysis of population-based data. The 80–125% confidence interval, derived from log-transformed AUC and Cmax values, ensures that the 90% confidence interval falls within this range-a requirement codified in the FDA’s 1992 Guidance for Industry. To dismiss this as ‘math magic’ is to misunderstand the foundational science of therapeutic equivalence.

I used to think generics were just cheaper versions until my dad, on warfarin, switched and started bruising like a grape. Turned out, it was a different manufacturer’s batch-same generic, different filler. He went back to the original brand, and the bruises stopped. Not because the drug was ‘better’-but because his body had adapted to that specific formulation. Consistency matters more than cost when your life’s on the line.

Have you ever wondered why the FDA approves generics from China but bans their food imports? Coincidence? Or is it that the same corporations that own the brand-name drugs also own the generic factories? They profit either way. The testing? A theater. The real goal is to keep you dependent on the system-so you never question why your insulin costs $300 when it’s made for pennies. Wake up.

Canada has stricter rules than the U.S.-we require bioequivalence testing for both fasting AND fed states, even for drugs that are supposed to be taken with food. So when Americans say ‘it’s fine,’ I just laugh. You’re letting your kids take pills tested under conditions that don’t match real life. That’s not science. That’s negligence dressed up as innovation.

My cousin in rural Kentucky gets her asthma inhaler through Medicaid. Brand name? $500 a month. Generic? $12. She’s been on it for two years. No ER visits. No complaints. She doesn’t know what AUC means. But she breathes. And that’s the whole point, isn’t it? Science should serve people-not the other way around.

There’s a quiet irony here: we demand perfect consistency from our medications, yet we accept wildly inconsistent human biology as normal. We’ll tolerate a 20% variation in drug absorption because ‘it’s natural,’ but we’ll sue a company for a 0.5% variance in a smartphone battery. We want science to be flawless-but only when it doesn’t inconvenience us. Maybe the real problem isn’t the generic pill… it’s our expectation of perfection in an imperfect world.

u r all overthinking this. i switched my zoloft generic last month and felt nothing. like, zero. maybe because i dont read reddit all day? just take the pill and live.

Let’s not forget: bioequivalence isn’t about perfection-it’s about equity. For every person who can afford to stick with a $400 brand-name drug, there are ten who can’t. That gap isn’t just financial-it’s life-or-death. The system isn’t flawless, but it’s the best we’ve got. And it’s saved millions from choosing between medicine and groceries. That’s not just science. That’s justice.