What Is Meniere’s Disease?

Meniere’s disease isn’t just dizziness. It’s a chronic inner ear disorder that messes with your balance and hearing, often without warning. The root problem? Too much fluid-called endolymph-building up in the tiny, delicate chambers of your inner ear. This isn’t normal water. It’s a potassium-rich fluid that helps your ear send signals to your brain about movement and sound. When it swells, it puts pressure on nerves and membranes, triggering the classic trio: spinning vertigo, ringing in the ear (tinnitus), and that heavy, full feeling like your ear’s stuffed with cotton.

It usually shows up between ages 40 and 60. About 1 in every 2,000 people has it. The condition was first described in 1861 by a French doctor, Prosper Ménière, but we’re still figuring out why it happens. No single cause fits everyone. For some, it’s poor drainage. For others, it’s immune system overdrive or even genetics. What we know for sure: it’s not just one thing. It’s a mix of fluid pressure, inflammation, and nerve damage working together.

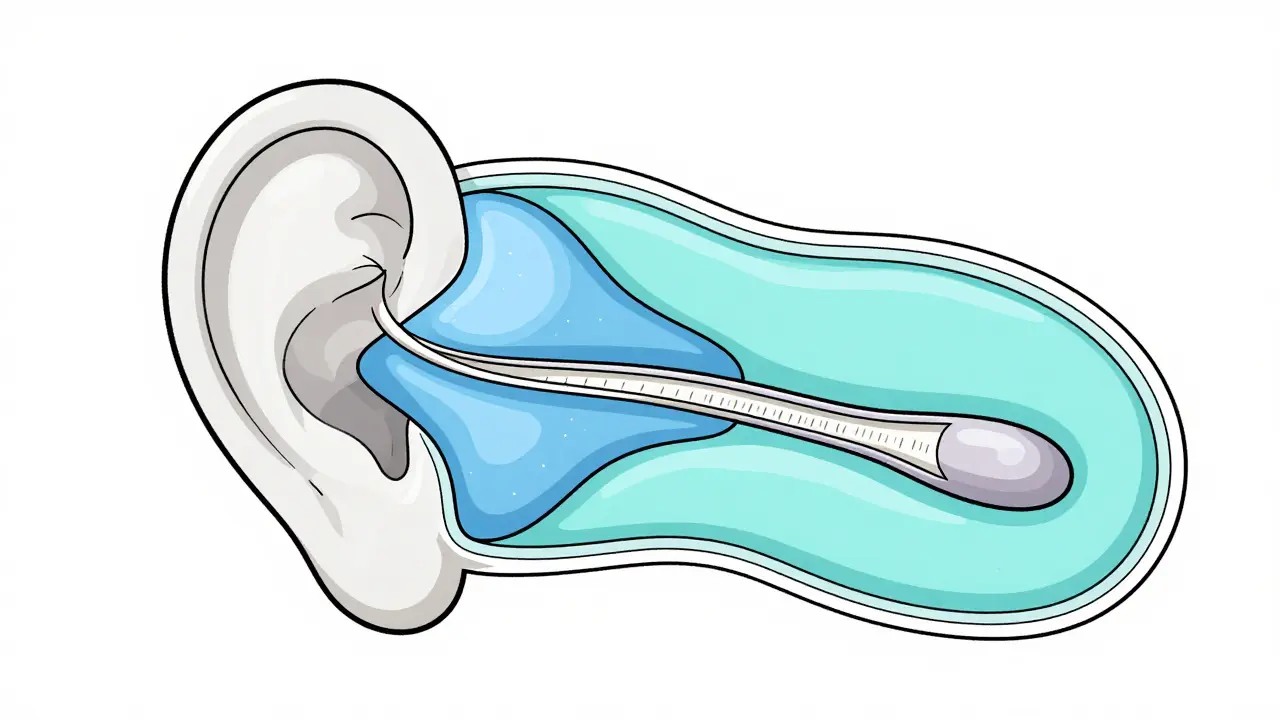

The Inner Ear’s Secret Fluid System

Your inner ear isn’t just one space. It’s two separate fluid systems running side by side. One is endolymph-potassium-rich, like seawater. It fills the membranous labyrinth: the cochlea for hearing, and the sacs and canals for balance. The other is perilymph-sodium-rich, like blood plasma. It wraps around the endolymph system like a protective shell. These fluids don’t mix. Their chemical balance is everything.

Endolymph is made mostly by the stria vascularis, a structure in the cochlea that works like your kidneys. That’s why cutting salt helps. When you eat less sodium, your body produces less endolymph. Studies show a low-sodium diet (1,500-2,000 mg per day) can reduce fluid buildup by up to 37%. The endolymphatic sac, a small pouch at the back of the inner ear, is supposed to drain the excess. But in 78% of severe cases, this sac’s drainage tube is too narrow-less than 0.3mm wide. Normal is 0.5-0.8mm. When drainage fails, pressure builds.

Recent 3D imaging shows the membrane walls in the inner ear aren’t all the same. The utricle (balance sensor) has thicker walls (12.5μm), so it swells less. The saccule and cochlear duct have thinner walls (8-9μm), so they bulge first. That’s why hearing loss and tinnitus usually come before full-blown vertigo. And there’s a valve-Bast’s valve-that normally keeps pressure in check. When it’s stuck open or torn, the sac ruptures under pressure, flooding the wrong areas and triggering attacks.

Why You Get Vertigo and Hearing Loss

When endolymph pressure spikes, it pushes Reissner’s membrane into the cochlea, squashing the hair cells that turn sound into nerve signals. That’s why your hearing drops suddenly-sometimes by 30-50 decibels-in just minutes. It’s not permanent at first. But after repeated attacks, those hair cells die. By 10 years, 38% of people have so much fluid that the inner ear is basically full. Attacks may stop, but you’re left with constant unsteadiness and permanent hearing loss. About 72% of long-term patients lose more than half their hearing in the affected ear.

Vertigo hits because the fluid pushes on the balance canals, tricking your brain into thinking you’re spinning. You might feel nauseous, vomit, or sweat. These attacks can last 20 minutes or all day. Afterward, you feel drained for hours or days. Tinnitus isn’t just noise-it’s often a low rumble or roar that changes with pressure. And the fullness? It’s like wearing earplugs that won’t come out.

The Immune System’s Role in Meniere’s

For years, doctors thought Meniere’s was purely mechanical-fluid pressure, no more. Now we know inflammation is a big part of it. New research shows immune cells in the inner ear go haywire. Dendritic cells pump out way too much IL-12, TNF-α, and IL-6-chemicals that turn on inflammation. This breaks down the blood-labyrinth barrier, letting immune cells flood in. T-cells stick around, causing long-term damage. In advanced cases, 68% of patients develop fibrosis-scar tissue-in the endolymphatic sac, making drainage even worse.

Fluid samples from the sac show inflammatory markers 10 to 20 times higher than in healthy people. IFN-γ and IL-17, two key inflammation drivers, are found at levels that clearly link to how bad the symptoms are. This explains why some people keep losing hearing even when their vertigo is controlled. The damage isn’t just from pressure-it’s from your own immune system attacking the inner ear.

First-Line Treatments: Diet and Diuretics

If you’ve been diagnosed, your first step is simple: cut salt. No more processed snacks, canned soups, or fast food. Aim for under 2,000 mg of sodium a day. That’s about half what most people eat. Studies show this alone reduces vertigo attacks by 40-50% in many people.

Diuretics like hydrochlorothiazide help too. They make your kidneys flush out extra fluid, which lowers endolymph production. About 55-60% of patients respond well. But it’s not magic. If your endolymphatic sac is too narrow or scarred, diuretics won’t fix it. Side effects? Low potassium, dizziness, dry mouth. You’ll need regular blood tests.

Some people also avoid caffeine, alcohol, and MSG. These can trigger attacks in sensitive people, though the evidence isn’t strong for everyone. Keeping a symptom diary helps spot your personal triggers.

Medications for Acute Attacks

When vertigo hits hard, you need fast relief. Oral steroids like prednisone can calm inflammation and reduce fluid buildup. They’re not for daily use, but a short 5-7 day course during an attack can cut the severity and length.

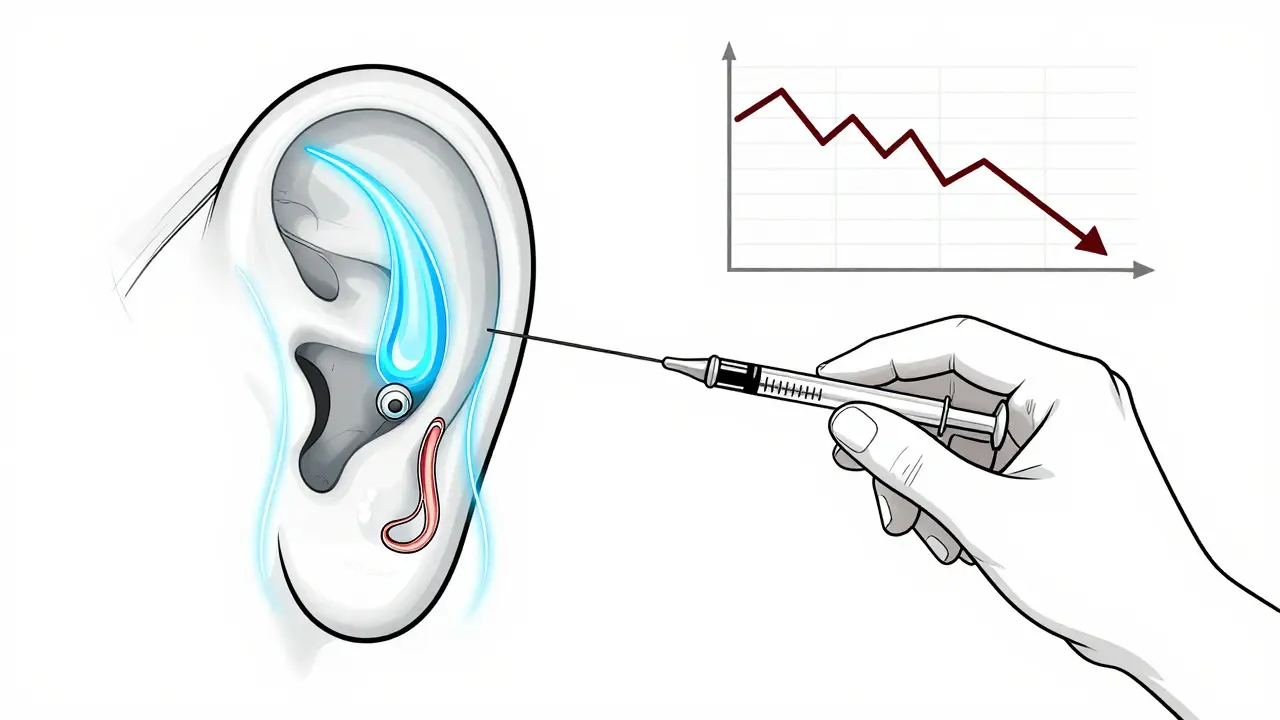

For more targeted treatment, doctors can inject steroids directly into the middle ear (intratympanic). A shot of methylprednisolone (40mg/mL) reaches the inner ear in hours. It works by tweaking ion channels and reducing fluid production. In studies, it controls vertigo in 68-75% of cases, with minimal risk to hearing.

For people who don’t respond, gentamicin injections are an option. This antibiotic kills the balance nerves in the inner ear-just enough to stop vertigo. It works in 85-92% of cases. But there’s a trade-off: 12-18% of people lose more hearing. It’s a last-resort move, usually only for those with already poor hearing in the affected ear.

New Hope: Immunotherapy and Emerging Treatments

The most exciting breakthroughs are coming from immunology. A 2025 study tested an anti-IL-17 antibody-drugs like secukinumab, already used for psoriasis and arthritis-in Meniere’s patients. After six months, vertigo attacks dropped by 63%. Hearing loss slowed by 41%. This isn’t a cure, but it’s the first treatment that targets the root immune problem, not just the symptoms.

Other research is looking at gene mutations. About 12% of familial cases involve SLC26A4 gene changes that mess with ion transport. Genetic testing isn’t routine yet, but it might help identify high-risk people before symptoms start.

3D imaging is also changing diagnosis. It can now detect fluid buildup before you even feel dizzy-with 89% accuracy. That means early intervention might prevent damage before it starts.

Surgery: When Other Options Fail

If attacks keep coming and you’re losing quality of life, surgery may be considered. Endolymphatic sac decompression is the most common. Surgeons open the bone around the sac to improve drainage. It helps vertigo in 60-70% of cases, but hearing improvement? Only 25-35%. It’s not a fix for deafness-it’s a way to reduce pressure.

For severe, one-sided cases, vestibular nerve section cuts the balance nerve from the brain. It stops vertigo in over 90% of cases and preserves hearing. But it’s major surgery-with risks like infection or facial nerve damage.

Labyrinthectomy removes the entire inner ear on one side. It cures vertigo completely, but you lose all hearing in that ear. It’s only done when hearing is already gone.

Long-Term Outlook: What Happens Over Time

Meniere’s isn’t static. It evolves. In the first 5 years, you’ll have wild swings-good weeks, bad weeks. After 10 years, many people stop having vertigo attacks. That sounds good, but it’s not. It means the inner ear is full, the membranes are stretched thin, and the hair cells are dying. You’re left with permanent imbalance, constant tinnitus, and hearing loss.

By 15 years, 93% of patients have hearing loss in both ears. That’s why early action matters. Controlling fluid and inflammation now can delay the point where damage becomes permanent.

Some people have “vestibular Meniere’s”-vertigo without hearing loss. That’s about 18% of cases. They often respond better to balance therapy and vestibular rehab.

Managing Daily Life

Living with Meniere’s means adapting. Avoid sudden head movements. Don’t drive during an attack. Use handrails. Install grab bars in the shower. Reduce stress-high cortisol levels can trigger flares. Sleep well. Stay hydrated. Avoid smoking.

Balance therapy helps. A physical therapist can train your brain to rely less on your damaged inner ear and more on your vision and body sense. Many people regain stability with regular exercises.

Support groups matter. Isolation makes it worse. Talking to others who get it-whether online or in person-helps you feel less alone.

When to See a Specialist

If you have recurring vertigo, hearing loss, or tinnitus that comes and goes, don’t wait. See an ENT doctor who specializes in balance disorders. Get an audiogram and possibly an MRI to rule out tumors or MS. Early diagnosis means early treatment-and that means protecting your hearing longer.

Can Meniere’s disease be cured?

There’s no cure yet. But symptoms can be managed effectively. Many people live full lives with fewer attacks through diet, medication, and lifestyle changes. Emerging immunotherapies show promise for slowing progression, but they’re still in clinical trials.

Does salt really affect Meniere’s symptoms?

Yes. Salt increases fluid retention, which worsens endolymph buildup. Studies show that cutting sodium to 1,500-2,000 mg per day reduces vertigo attacks by up to 50%. It’s one of the most effective, low-risk tools you have.

Why do I lose hearing during an attack?

The excess fluid pushes on Reissner’s membrane, squashing the hair cells in the cochlea that turn sound into signals. This causes temporary hearing loss. Repeated attacks damage these cells permanently, leading to lasting hearing decline.

Is Meniere’s disease hereditary?

About 10-15% of cases run in families. Researchers have found 17 gene variants linked to Meniere’s, especially those affecting how ions move in and out of inner ear cells. If close relatives have it, your risk is higher.

Can stress trigger Meniere’s attacks?

Yes. Stress raises cortisol and adrenaline, which can disrupt fluid balance in the inner ear and trigger attacks. Managing stress through sleep, exercise, or therapy can reduce frequency.

Will I go completely deaf?

Not necessarily. Many people keep usable hearing for years. But over time, especially without treatment, hearing loss tends to worsen. About 72% of long-term patients lose more than half their hearing in the affected ear. Early intervention improves your chances of preserving it.